Introduction

Central nervous system (CNS) tumours are a major cause of mortality and morbidity in adults. These tumours are classified as primary when originating from intracranial cells, or secondary when they originate from another organ and metastasise to the brain.

In the United States, approximately 80,000 new cases of primary brain tumours are diagnosed annually, with gliomas accounting for 31% of cases, representing the most common primary CNS tumour in adults. Gliomas also constitute 81% of malignant brain and CNS tumours, with around 20,000 new cases diagnosed each year [1,2].

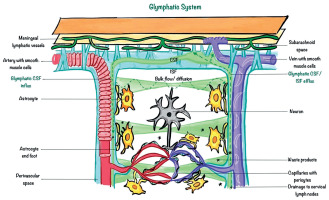

The glymphatic system was first described by Iliff et al. in 2012 [3] as the brain’s waste clearance mechanism, facilitating the exchange of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and interstitial fluid (ISF) via perivascular spaces (Figure 1). Astrocytic endfeet, containing aquaporin-4 (AQP4) channels, plays a critical role in this process by regulating fluid dynamics (Figure 2). Disruption of this system can impair waste clearance and exacerbate disease progression [3-5].

Figure 1

Illustration of the glymphatic system’s role in clearing waste from the central nervous system, highlighting the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and interstitial fluid (ISF) through perivascular spaces and astrocytic end-feet

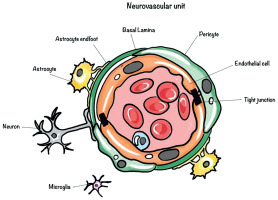

Figure 2

Illustration of the neurovascular unit, highlighting its components, including neurons, astrocytes, astrocytic end-feet, microglia, pericytes, endothelial cells, tight junctions, and the basal lamina, which together maintain the blood-brain barrier and regulate brain homeostasis

A novel imaging method, the diffusion tensor image analysis along the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS) index, obtained using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), quantifies diffusivity along perivascular spaces, enabling the assessment of glymphatic function. It measures water diffusivity along perivascular spaces, particularly in regions near the lateral ventricles. The index leverages the unique anatomical alignment of fibre tracts to isolate diffusivity along the perivascular axis [6]. Alterations in glymphatic flow have been linked to various neurological conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease [6-9], normal pressure hydrocephalus [10,11], idiopathic intracranial hypertension [12-14], stroke [15-17], and traumatic brain injury [18-20].

In brain tumours, glymphatic dysfunction can result from mass effect and blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption, contributing to peritumoral oedema and altered fluid dynamics. Reduced AQP4 expression near gliomas further impairs CSF-ISF exchange, promoting inflammation and tumour progression [21-23].

Glymphatic system dysfunction has been investigated concerning the development of peritumoral brain oedema in gliomas, meningiomas, lymphomas, and metastases [21-23]. Numerous studies have examined the impact of IDH mutation status and tumour grade in gliomas, revealing a progressive decrease in the DTI-ALPS index with increasing glioma grade. Additionally, IDH1 wild-type gliomas are associated with a lower DTI-ALPS index, reflecting greater glymphatic dysfunction [23,24].

Existing research on glymphatic dysfunction across various tumour types, particularly gliomas and metastases, remains limited. This study investigates glymphatic dysfunction in high-grade gliomas (HGGs), low-grade gliomas (LGGs), and metastases using the DTI-ALPS index. It focuses on evaluating changes in the DTI-ALPS index concerning tumour volume, peritumoral oedema, the tumour volume-to-total brain volume ratio (TV/TBV), and the peritumoral oedema-to-total brain volume ratio (PTE/TBV) in these 3 tumour groups. We propose that the aggressive and infiltrative nature of HGGs may influence glymphatic function distinctly when compared to LGGs and metastases. A deeper understanding of these mechanisms may shed light on tumour progression and pave the way for developing therapeutic strategies targeting glymphatic pathways.

Material and methods

Study design

This retrospective study received approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee. Imaging data from patients were retrospectively analysed between March 2020 and July 2024. The study included patients who met the following criteria: (I) age 18-65 years; (II) pathologically confirmed supratentorial gliomas/metastases; (III) had undergone preoperative DTI evaluation; and (IV) had not received any treatment (surgery/radiotherapy/chemotherapy) before imaging. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images of poor quality; (II) tumours with the following imaging characteristics – lesions that extended across the midline, purely cystic, intraventricular/infratentorial location, causing a significant mass effect on the lateral ventricles; (III) projection/association fibres destroyed by the tumour; (IV) outside the specified age range; and (V) general contraindications to MRI. Midline tumours were excluded because they distort the normal anatomy required for accurate assessment of the DTI-ALPS index, leading to unreliable or non-interpretable index values.

At our institution, a cohort of 87 patients diagnosed with a supratentorial tumour underwent preoperative DTI. Seven individuals were excluded due to poor-quality MRI images (n = 2) or gliomas crossing the midline (n = 5). The final study population consisted of 80 histopathologically verified intracranial tumours: 30 LGGs (World Health Organization grades I-II), 30 HGGs (grades III-IV), and 20 brain metastases. Among the 60 glioma cases, 43 exhibited IDH mutations, while the remaining 17 were IDH wild-type. The screening process is shown below (Figure 3).

Data acquisition

All images were obtained using a 3.0 Tesla magnetic resonance scanner (Discovery MR750, GE HealthCare) equipped with a head coil consisting of 48 channels. The standard MRI sequence consisted of DWI (b = 1000), T1 BRAVO (TR/TE, 7700/1000 ms), T2 (TR/TE, 5742/1000 ms), T2 FLAIR (TR/TE/TI, 7500/120/1000 ms) sequences with matrix 256 × 256, FOV 24 × 24 (frequency and phase FOV), and slice thickness of 1.8 mm. Post-IV-contrast T1 and FLAIR sequences were performed using gadolinium-based contrast (gadobuterol) (0.5 ml/kg [0.1 mmol/kg] body weight at a flow rate of approximately 2 ml/s, with a maximum dose of 10 ml).

DTI data were acquired using a single-shot echo-planar imaging sequence (TR/TE: 3941/1000 ms) with parallel imaging, incorporating 2 strong encoding gradients based on the Stejskal-Tanner method [25]. Diffusion gradients were applied in 50 directions with b-values of 0 and 1000 s/mm². The imaging parameters included a frequency FOV of 26, a phase FOV of 1, an excitation number (NEX) of 1, and a data matrix of 128 × 128. Thirty-eight slices were captured, with a slice thickness of 3 mm and no interslice gap, resulting in a total scan time of approximately 3-4 minutes.

Image post-processing and analysis

The DTI images were post-processed using DTI analysis software on a General Electric (GE) Advantage Workstation (AW) Model 4.7. The DTI-ALPS index was determined via DTI advanced analysis software on a GE AW 4.7.

The glymphatic function was evaluated using the DTI-ALPS approach. This approach assesses the diffusivity along the perivascular space on an axial slice located at the lateral ventricle body level. Perpendicular to the ventricular walls at the surface of the lateral ventricular bodies, the medullary veins, along with perivascular spaces, run in a right-left or left-right direction (x-axis). At this level, the fibres of the corona radiata (projection fibres) are present lateral to the body of lateral ventricles in the craniocaudal direction (z-axis). Located laterally to the corona radiata, the superior longitudinal fascicle, which corresponds to the association fibres, extends in the anterior-posterior direction (y-axis). Colour-coded maps were used to designate circular regions of interest (ROIs) with a diameter of 5 mm on the association fibres and projection fibres of the affected hemispheres at the level of the lateral ventricular body. The medullary veins’ alignment is parallel to the body of the lateral ventricle [21]. An illustration of ROI placement is presented (Figures 4-6). Given that the perivascular space is almost perpendicular to both the projection fibres and association fibres, the average diffusivity in the x-axis of both fibres can indicate the variation in perivascular flow. Normalisation of mean diffusivity is done [6].

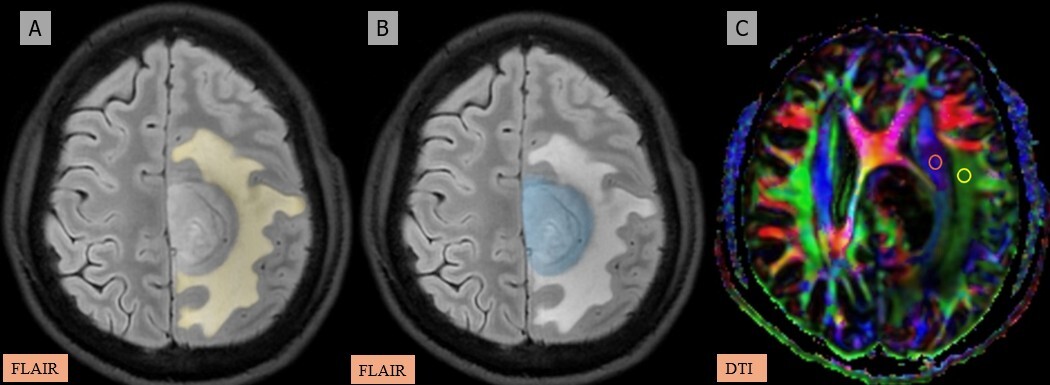

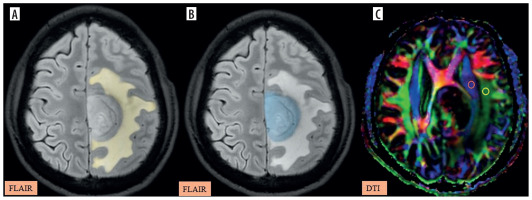

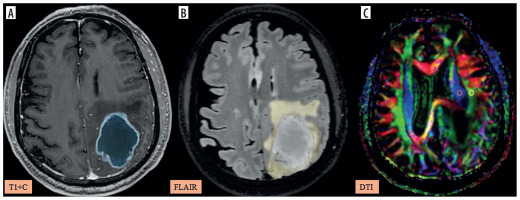

Figure 4

A-C) Patient with a low-grade glioma in the left frontal region presenting with headache and seizures. A) and B) Axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images show the segmented peritumoral oedema (yellow) and tumour volume (blue). C) Image describing the calculation of the diffusion tensor image analysis along the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS) index using two regions of interest (ROIs) drawn within the projection (blue) and association (green) fibres in the left periventricular region

Figure 5

A-C) Patient with high-grade glioma in the left parietal region presenting with right-sided weakness. A) Axial post-contrast T1 image shows the segmented tumour volume (blue). B) Axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) image shows the segmented peritumoral oedema (yellow). C) Image describing the calculation of the diffusion tensor image analysis along the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS) index using two regions of interest (ROIs) drawn within the projection (blue) and association (green) fibres in the left periventricular region

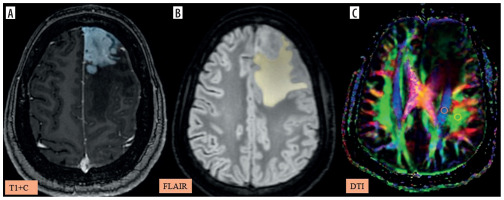

Figure 6

A-C) Patient with metastasis in the left frontal region presenting with right lower limb weakness and disorientation. A) Axial post-contrast T1 image shows the segmented tumour volume (blue). B) Axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) image shows the segmented peritumoral oedema (yellow). C) Image describing the calculation of the diffusion tensor image analysis along the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS) index using two regions of interest (ROIs) drawn within the projection (blue) and association (green) fibres in the left periventricular region

where: Dx proj – diffusivity along the x-axis in projection fibres, Dx assoc – diffusivity along the x-axis in association fibres, Dy proj – diffusivity along the y-axis in projection fibres, Dz assoc – diffusivity along the x-axis in association fibres.

Segmentation and volumetric analysis

Tumour segmentation was conducted using the 3D Slicer platform with the open-source automated software Raidionics [26] (https://github.com/raidionics/raidionics). All segmentation results were carefully reviewed, and any incorrectly delineated tumour regions were corrected through manual adjustment. The output parameters included tumour volume, peritumoral oedema, TV/TBV, and PTE/TBV.

A blinded radiologist with 5 years of experience (SRK) independently conducted all the measurements without knowledge of the clinical and histological data. Representative images of DTI ALPS index calculation and tumour segmentation in LGG, HGG, and metastasis are provided in Figures 4-6.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Jamovi software version 2.4 [27]. Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), median, and range. The normality of parameters, including the DTI-ALPS index, was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilks test. A comparison of the DTI-ALPS index between types of tumours using one-way ANOVA (Welch’s test), followed by the Tukey post-hoc test, was performed for pairwise comparisons. Additionally, the DTI-ALPS index was compared between IDH1 mutant and IDH1 wild-type gliomas using Student’s t-test.

The relationships between the DTI-ALPS index and tumour-associated oedema, peritumoral oedema, the tumour volume-to-total brain volume ratio (TV/TBV), and the peritumoral oedema-to-total brain volume ratio (PTE/TBV) across the 3 tumour groups were analysed using a correlation matrix and Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) or Spearman’s correlation coefficient (ρ). All tests were considered statistically significant for a p-value < 0.05.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to determine the diagnostic accuracy of the DTI-ALPS index for differentiating LGG and HGG. Metastases were included in the overall comparison but not the binary classification ROC analyses. Optimal thresholds were derived using the Youden Index. Area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, and 95% confidence intervals were reported for each classification.

Results

Eighty patients with pathologically confirmed gliomas and metastases were included, 30 of whom were diagnosed with LGGs (grades I and II), 30 with high-grade gliomas (grades III and IV), and 20 with metastases (primary site: 7 – lung, 5 – colon, 5 – breast, 3 – head and neck). Of the 60 gliomas analysed, 43 harboured IDH mutations, whereas the remaining 17 maintained a wild-type IDH status. The patient demographics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1

Demographics

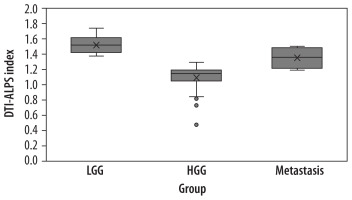

The one-way ANOVA (Welch’s test) showed a statistically significant difference in the DTI-ALPS index between the groups, with an F-value of 51.2, degrees of freedom (df1 = 2, df2 = 30.3), and a p-value of < 0.001. The Tukey post-hoc test was further performed to identify specific group differences. Significant differences were observed between all pairs of tumour groups (LGG vs. HGG, LGG vs. metastases, and HGG vs. metastases). The mean difference between LGG and HGG was 0.435 (p < 0.001); between LGG and metastases it was 0.172 (p = 0.005); and between HGG and metastases the mean difference was –0.264 (p < 0.001). The mean for HGG is the lowest, followed by metastases and then LGG.

A box plot illustrates the distribution of the DTI-ALPS index across these 3 tumour groups (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Box plot comparing the diffusion tensor image analysis along the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS) index across 3 groups – low-grade gliomas (LGG), high-grade gliomas (HGG), and metastases. Outliers in the HGG group are represented by grey dots

Furthermore, the mean DTI-ALPS index in IDH1 wild-type gliomas (1.23 ± 0.08, n = 17) was significantly lower than that observed in IDH1 mutant tumours (1.42 ± 0.10; n = 43, p < 0.001), implying greater glymphatic impairment in wild-type gliomas and supporting the potential of IDH1 mutation status as a biomarker for differential glymphatic function.

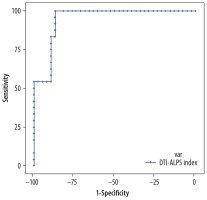

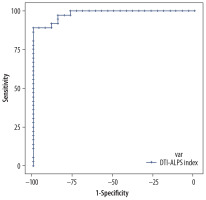

The DTI-ALPS index’s diagnostic performance was assessed using ROC curve analysis to differentiate these 3 tumour groups. The DTI-ALPS index of > 1.3838 demonstrated excellent diagnostic capability, with an AUC of 0.97, a sensitivity of 100%, and a specificity of 86.64%, indicating that the ALPS index is a reliable predictor for LGG (Figure 8). Similarly, a DTI-ALPS index of < 1.317 is a reliable predictor for HGG, with an AUC of 0.982, a sensitivity of 88.89%, and a specificity of 100% (Figure 9).

Figure 8

Receiver operating characteristic curve for the the diffusion tensor image analysis along the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS) index in the low-grade glioma (LGG) group, illustrating its diagnostic performance by plotting sensitivity against 1-specificity, showing excellent sensitivity and specificity for a cut-off of > 1.3838

Figure 9

Receiver operating characteristic curve for the the diffusion tensor image analysis along the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS) index in the high-grade glioma (HGG) group, illustrating its diagnostic performance by plotting sensitivity against 1-specificity, showing excellent sensitivity and specificity for a cut-off of < 1.317

The Shapiro-Wilks test showed that tumoural volume and TV/TBV were not normally distributed. Hence, non-parametric tests were used for correlation of the 2 variables with the DTI-ALPS index (Spearman’s rho). For peritumoral oedema and PTE/TBV, parametric tests were used (Pearson’s r).

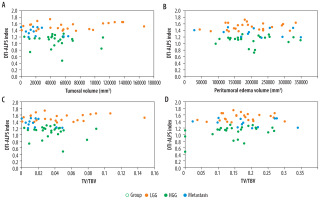

There was no significant association between the DTI-ALPS index and tumour volume, peritumoral oedema, TV/TBV, and PTE/TBV among the 3 tumour groups. Table 2 shows these results. Scatter plots describing the relationship between the DTI-ALPS index and different parameters among the tumour groups are described in Figure 10 A-D.

Table 2

Correlation between the the diffusion tensor image analysis along the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS) index and tumour volume, peritumoral oedema, the tumour volume-to-total brain volume ratio (TV/TBV), and the peritumoral oedema-to-total brain volume ratio (PTE/TBV) among the 3 groups (significant p-value < 0.05)

Figure 10

A-D) Scatter plot describing the relationship between the diffusion tensor image analysis along the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS) index and tumour volume (A), peritumoral oedema (B), the tumour volume-to-total brain volume ratio (TV/TBV) (C), and peritumoral oedema to tumour volume ratio (PTE/TBV) (D) across 3 tumour groups: low-grade glioma (LGG), high-grade glioma (HGG), and metastasis. No significant correlation is seen among these parameters

Discussion

This study assessed glymphatic dysfunction in LGG, HGG, and metastases by evaluating the DTI-ALPS index. The results demonstrate significant differences in the DTI-ALPS index among these groups, highlighting its potential as a biomarker for assessing tumour-induced alterations and helping in further understanding glymphatic function.

The findings in our study align with previous research indicating a progressive decline in glymphatic function with increasing glioma grade [23,24]. HGGs showed the lowest DTI-ALPS index compared to LGGs and metastases, suggesting severe glymphatic impairment. This reduction may reflect BBB disruption, tumour angiogenesis, and decreased and misplaced AQP4 expression secondary to increased tumour aggressiveness and parenchymal infiltration [28-31]. Multiple studies using mouse models have demonstrated similar findings, showing that a reduction in AQP4 limits CSF-ISF exchange, leading to the accumulation of inflammatory and immunological substances generated by tumour cells [28,32,33].

The distinct pathogenic mechanisms behind these tumour types may account for the greater DTI-ALPS index in metastases compared to HGGs, as they exhibit less infiltrative behaviour than HGGs and may have a less significant effect on the lymphatic system. Furthermore, in the early stages of metastases, the BBB is usually intact or only slightly compromised, which may restrict its influence on glymphatic flow and ISF dynamics [21,34-36] tumor fractional anisotropy.

The glymphatic system may be comparatively conserved because LGGs are less aggressive and infiltrative than HGGs. Though less severe, glymphatic dysfunction persists because tumour-induced astrocytic modifications and moderate BBB abnormalities may still cause LGGs to disturb local balance [37,38]. Between the less invasive metastases and the extremely aggressive HGGs, the intermediate DTI-ALPS index in LGGs corresponds to their intermediate pathogenic features.

Interestingly, no significant association was found between the DTI-ALPS index and tumour-associated oedema, peritumoral oedema, the TV/TBV, or the PTE/TBV among the 3 tumour groups. These findings are contrary to several prior studies in which an association was found between peritumoral oedema volume and reduced glymphatic function in various brain tumours [21-24,31,39,40]. Mechanisms for the peritumoral oedema formation in brain tumours include disruption of the BBB, increased vascular permeability secondary to angiogenic factors like vascular endothelial growth factor, and dysregulated expression of AQP4. Therefore, peritumoral oedema is predominantly caused by vascular and oncogenic processes, while glymphatic dysfunction primarily occurs in poor clearance of metabolic waste and solutes. Hence, glymphatic dysfunction may have a secondary or indirect effect on the formation of peritumoral oedema [34,36,41,42]. Since the DTI-ALPS index is based on measurements near the lateral ventricles, it might not accurately represent glymphatic dysfunction in more distal regions affected by peritumoral oedema. The morphology of the periventricular veins may also change because of changing tumour sites, and mass effects may influence the measurement of diffusivity along the perivascular spaces on the ipsilateral side. No studies to date have specifically investigated whether there is a relation between glymphatic function and the location of a tumour.

The DTI-ALPS index demonstrated exceptional diagnostic performance in differentiating between the 3 tumour groups; a DTI-ALPS index value of < 1.317 was a strong predictor of HGGs, while a value of > 1.3838 consistently identified LGGs with high sensitivity and specificity. These cutoff points demonstrate the clinical utility of the DTI-ALPS index as a non-invasive imaging biomarker for tumour grading that can be used in conjunction with traditional and multiparametric MRI imaging and histological analysis.

The observed glymphatic dysfunction in gliomas and metastases highlights the need for therapeutic interventions targeting the glymphatic system. Restoring glymphatic flow may improve waste clearance, reduce peritumoral oedema, and mitigate tumour-associated inflammation, potentially enhancing treatment outcomes [28]. Future studies investigating the impact of glymphatic modulation on tumour progression and therapeutic response are warranted.

Limitations

There are multiple limitations to this study. The single-centre, retrospective study design has the potential to introduce selection bias. Second, excluding tumours causing significant mass effects or crossing the midline may limit the generalisability of the findings to all brain tumours. Finally, the DTI-ALPS index offers useful information about glymphatic dysfunction but fails to capture the dynamic elements of CSF-ISF exchange, which may require sophisticated imaging techniques such as dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI using gadolinium/radionucleotide-labelled CSF tracers.

The pathophysiology of these tumour-associated glymphatic alterations should be further studied by future multicentric research studies that examine the relationship between glymphatic dysfunction and tumour location, size, and molecular markers; the relationship between glymphatic dysfunction and the development of peritumoral oedema must be studied in time; and longitudinal studies that examine changes in the DTI-ALPS index before and after treatment may shed light on the effects of therapeutic interventions on glymphatic function.

Conclusions

The DTI-ALPS index is a promising biomarker for evaluating tumour-induced changes in glymphatic function, and this study emphasises the important role that glymphatic dysfunction plays in gliomas and metastases. The results highlight the potential of using the DTI-ALPS index in standard clinical practice for tumour grading. Future research focusing on therapeutic options that target the glymphatic system may make novel approaches to improving outcomes for patients with brain tumours.