Introduction

Advances in diagnosis and treatment of neoplasms have led to higher cure rates with 5-year survival rates reaching approximately 80% [1], but the cost of this progress is that patients who have survived one cancer may develop another one. Treatment of primary malignant neoplasms is a complex process, divided into three, often complementary components: surgery, chemotherapy, and irradiation. Depending on the age of the patient, type of malignancy, and its stage, an appropriate therapeutic program is introduced. Surgical procedures are the only method of treatment without the risk of teratogenic and carcinogenic complications, but unfortunately are not always sufficient or even applicable. The remaining methods, i.e. chemotherapy and radiotherapy, are burdened with such complications. The risk of developing a subsequent neoplasm is very difficult to determine; it is estimated that in previously treated oncology patients, the risk is 10 times higher than in the general population [1]. In children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), it is estimated to be 14 times higher than in the general population [2].

The terminology related to this topic that can be found in the literature is very confusing, and the terms “second” and “secondary” tumor (ST) are often used interchangeably and incorrectly [3].

The definition of multiple primary malignancies, as provided by the International Agency for Research on Cancer in 1991, implies that the following conditions must be met for the diagnosis of a second primary tumor (SPT):

histopathological examination confirming the malignant nature of both tumors: the primary one (index tumor – IT) and SPT,

separate location of both tumors, and if they are located in the immediate vicinity, a minimum of 2 cm of healthy tissue separating them,

if the SPT develops in the same organ, a minimum of 5 years must have elapsed since the diagnosis of the first tumor,

the histopathological features should exclude the possibility that the second tumor is a metastatic lesion from the primary focus.

Taking into account the time factor, there are two types of SPT:

synchronous – tumors diagnosed within 6 months of the diagnosis of the primary tumor focus,

metachronous – tumors diagnosed more than 6 months after the diagnosis of the primary tumor focus.

ST is a new malignancy that occurs in an individual as a result of previous treatment with radio- or chemotherapy.

The general term “subsequent malignant neoplasm” (SMN) seems therefore to be the most reasonable name to cover both types of malignancy.

The Institute of Mother and Child in Warsaw is a tertiary referral center for pediatric solid tumors. Our patients are treated and then followed up, and survivors of other childhood malignancies that developed bone or soft tissue sarcomas as a subsequent tumor are referred to us from other centers.

The purpose of this study was to count and review the cases of SMNs in our material.

Material and methods

We retrospectively reviewed the patients’ charts in order to detect children with secondary, second, third, and fourth malignancies.

The following data were analyzed: gender, age at diagnosis, treatment, time between the diagnoses, association of subsequent cancer with a history of radiotherapy, time of observation, status: alive or dead at the time of manuscript preparation, and genetic background.

Results

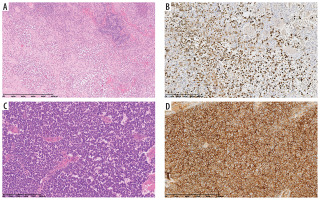

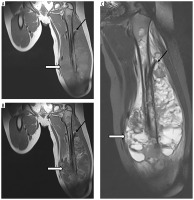

There were 60 patients in the analyzed material (29 girls and 31 boys). All histopathological diagnoses were established or confirmed by consultation in our center (Figure 1). Median age at the time of diagnosis of the IT was 6.8 years (range 0.1-22.1 years). In patients with optic glioma as the IT (n = 4), no treatment was undertaken. Median age at the time of diagnosis of a subsequent neoplasm was 14.9 years (range 2.1-36.6 years). Median time between the diagnosis of a first and subsequent neoplasm was 6.3 years (range 0.8-36.2 years). Four patients had the second primary neoplasm diagnosed before the end of treatment of the first one (no later than 13 months after the first diagnosis): 2 of them had Ewing sarcoma (ES) and acute myeloblastic leukemia, 1 had osteosarcoma (OS) and astrocytoma (Figure 2), and 1 had ES and myelodysplastic syndrome.

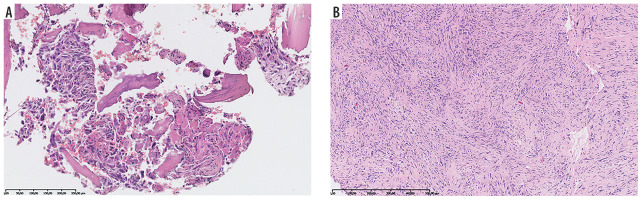

Figure 1

A 10-year-old patient (No. 49). Langerhans cell histiocytosis [A – HE, B – IHC: Langerin (+)]. At the age of 11 years Ewing sarcoma [C – HE, D – IHC: CD99 (+)]

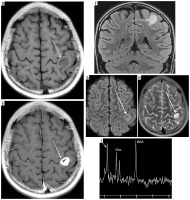

Figure 2

A 10-year-old patient (No. 38) with osteosarcoma of the left femur (thick white arrows). A) T1-weighted coronal image before, and B) after contrast medium administration, C) STIR coronal image. Thin black arrows indicate an intramedullary nail, placed as part of the first treatment of a pathological fracture At the age of 11 years brain imaging was performed due to headache and dizziness and a metastasis was suspected although atypical (thin white arrows) – a single enhancing lesion. D) T1-weighted axial image before, and E) after contrast medium administration, without strong diffusion restriction (G – DWI sequence). Very small edema around the lesion (F – FLAIR coronal image, H – T2-weighted axial image) may be due to treatment with mannitol which was implemented after the preceding CT; the same might have caused an unusual peak on proton MR spectroscopy at 3.8-3.9 ppm (I). Attention is drawn to the unreduced peak of N-acetyl-aspartate (NAA) and the unincreased choline (Cho) peak. Pathological diagnosis was pilocytic astrocytoma

Out of 60 patients, 27 received radiotherapy in the treatment of the IT [or the second one: in 1 patient with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) it was the third neoplasm that developed in the irradiation field of the second one]. In 16 of them there were STs that developed in the irradiated site (Figure 3). Median time from the first to the secondary, radiotherapy-induced tumor was 6.9 years (range 2.4-16.3 years).

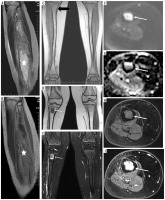

Figure 3

A 7-year-old patient (No. 50) with Ewing sarcoma of the right fibula (asterisks): A) T2-weighted sagittal image, B) T1-weighted sagittal image with contrast enhancement. Follow-up study after 6 months, after surgery and radiotherapy, no lesions (thick black arrow): C) coronal T1-weighted image. Pleomorphic sarcoma of the right tibia 3.9 years later (thin white arrows): D) coronal T1-weighted image, E) T2-weighted image with fat saturation, F) axial DWI, G) corresponding ADC map, confirming diffusion restriction, axial T1-weighted images before (H) and after (I) contrast medium administration

In a group of patients without radiation-induced tumors (the remaining 44 patients), SPT was diagnosed. Median time between the diagnosis of the first and SPT was 6.0 years (range 0.8-36.2 years).

In the analyzed material there are 11 patients (18.3%) with cancer predisposition syndromes (CPS), including 3 with RB1 mutation (Nos. 10, 12, 36), 5 with Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS, Nos. 12, 18, 29, 48, 56), and 4 with NF1 (Nos. 53, 54, 55, 59). One girl (No. 12) had 2 CPS: LFS and mutation in the RB1 gene.

Four patients (3 with CPS) had third malignant neoplasms:

two girls with LFS: patient No. 48 had 1) rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) in the behind-the-ear area, 2) OS of the tibia, 3) high-grade pleomorphic sarcoma of the calf (Figure 4); patient No. 29 had 1) RMS, 2) chondrosarcoma (ChS), 3) ALL,

one boy with NF1, patient No. 55: 1) optic glioma, 2) malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) of the calf, 3) ependymoma in the spinal canal (Figure 5),

one boy without a known CPS, patient No. 3: 1) RMS, 2) OS, 3) ALL.

Three girls had fourth malignant neoplasms:

Figure 4

A 14-year-old patient (No. 48) with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. A) Second tumor – high-grade conventional osteosarcoma (HE). B) Third tumor – undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (HE)

Figure 5

NF1 patient (No. 55). Optic chiasm glioma (thick arrows) known since the age of at least 14 years (first available brain MRI): A) T2-weighted sagittal image, B) coronal FLAIR section. MPNST (marked with “T”) of the right calf at the age of 20: C) coronal T1-weighted image with fat saturation and contrast enhancement. Ependymoma (asterisk) of the spinal canal at the age of 22: D) sagittal T2-weighted image. Thin arrows indicate multiple neurofibromas

patient No. 6 without a known CPS: 1) ovarian germ cell tumor, 2) ChS of the femur, 3) thyroid cancer, 4) ALL,

patient No. 36 with RB1 mutation: 1) retinoblastoma (RBL), 2) OS of the femur, 3) thyroid cancer, 4) melanoma,

patient No. 53 with NF1: 1) optic glioma, 2) RMS, 3) MPNST, 4) ALL.

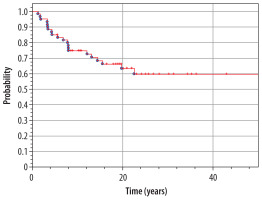

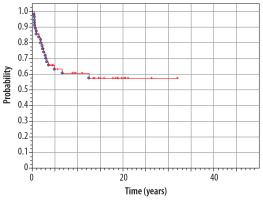

At the moment of preparing this manuscript, 37 patients are alive (61.6%), and 23 (38.4%) have died. Median time of observation of patients from our material is 15.0 years (range 1.3-43.1 years). The overall 5-year survival rate in the whole analyzed group (n = 60) is 85% from the diagnosis of IT until now (Figure 6). The overall 5-year survival rate from the diagnosis of the second tumor is 63% (Figure 7).

Detailed patients’ data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Detailed patients’ data in our study group

[i] npl – neoplasm, CHT – chemotherapy, RTX – radiotherapy, ca – carcinoma, sa – sarcoma, tu – tumor, ALL – acute lymphoblastic leukemia, RMS – rhabdomyosarcoma, GCT – germ cell tumor, SySa – synovial sarcoma, AML – acute myeloblastic leukemia, RBL – retinoblastoma, MDS – myelodysplatic syndrome, HBL – hepatoblastoma, MFH – malignant fibrous histiocytoma (nowadays: undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, UPS), PNET – primitive neuroectodermal tumor, MNTI – melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy, NBL – neuroblastoma, PA – pilocytic astrocytoma, LCH – Langerhans cell histiocytosis, PBS – pleuropulmonary blastoma, OPG – optic pathway glioma, MPNST – malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor

Discussion

The extensive analysis of SMN was published in 2010. The authors analyzed a large cohort of 14 359 five-year childhood cancer survivors, of whom 1402 subsequently developed 2703 neoplasms. The risk of a subsequent neoplasm was the highest in patients surviving Hodgkin lymphoma, with ES in the second place. The most frequent subsequent malignancies were nonmelanoma skin cancer and breast cancer. The incidence increased with extended follow-up. Radiation therapy increased risk of all subsequent neoplasms; the risk was also associated with exposure to chemotherapy (e.g. anthracyclines, alkylating agents), hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and genetic predisposition [4,5].

In a more recently published study, the risk of having a SPT in childhood cancer patients was found to be more than 10-fold higher than the risk of having a neoplasm in the general population [6]. The number of SMN has been increasing constantly; it is estimated that they constitute approximately 16.7% of all reported cases. Anti-cancer treatment is considered by some authors as the main cause (70% appear within the radiation field), followed by genetic susceptibility and exposure to environmental factors, such as smoking [7].

Another study found that CPS were the strongest predictor of SPTs; 22% of patients with early SPTs were diagnosed with CPS, while SPTs were found in about 8% of the general childhood cancer population [6].

The following chemotherapeutic agents are well known to be associated with increased risk of a subsequent malignancy:

alkylating agents (mechlorethamine, chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide, melphalan, lomustine, carmustine, busulfan),

platinum-based drugs (cisplatin, carboplatin),

anthracycline topoisomerase II inhibitors (etoposide or VP-16, teniposide, mitoxantrone).

It is also well known that the higher the doses, the higher the doses over a shorter time period, and the longer the treatment time, the higher is the risk of a subsequent malignancy.

However, while it seems obvious that a new malignancy developing in the radiation field is radiation-induced and is a ST, it is more difficult to prove that a metachronous second tumor is in fact a secondary, chemotherapy-induced one. Therefore, for the purpose of this study, only new tumors in the radiation field were considered as clearly secondary ones.

All 16 STs in our material fulfilled the criteria of radiation-induced sarcoma as described by Cahan et al. [8]: 1) radiation must have been delivered to the site in question; 2) the new malignancy must arise within the irradiated field; 3) the new tumor must be histologically distinct from the original primary lesion; and 4) the latent period between the time of radiation exposure and development of the new malignancy must be several years. In our material, the median time between the IT and the secondary one was 6.9 years. This time is longer than 5 years – the period after which the patient is considered cured in many centers. It is therefore postulated that for childhood malignancies, the cured patient should be followed up for the rest of his/her life [9].

It should be stated here that not only malignant tumors arise as a consequence of radiotherapy. For example, cranially irradiated leukemia patients develop meningiomas [10]. Schwannomas are reported less frequently, following whole body irradiation for a childhood primary malignancy [11,12]. In our material there is one patient (No. 58) with a benign tumor: schwannoma in the lumbar-sacral part of the vertebral column after whole neuraxis irradiation for ALL.

Most of our patients (n = 51, 85%) underwent surgery at a certain stage of treatment of their first tumor, except those with optic gliomas (n = 4), leukemia (n = 4), and Langerhans cell histiocytosis (n = 1). On follow-up radiological studies – plain films, ultrasound (US), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (occasionally on computed tomography – CT) – the evolving post-operative and post-radiotherapy lesions were observed over time. When a new or different appearance was noted, oncological suspicion was raised, leading to more frequent follow-up or imaging by another method. This, in turn, led to biopsy, the site of which was selected on the basis of imaging studies and sometimes performed under imaging control, usually US.

Patients carrying mutations for hereditary cancer syndromes are at high risk not only for the development of tumors at an early age, but also for the synchronous or metachronous development of multiple tumors of the corresponding tumor spectrum [13]. In our material we have 5 patients with LFS, belonging to genetic instability/DNA repair syndromes. It is a rare inherited autosomal dominant disorder, associated with mutations in three genes, most commonly involving the tumor suppressor protein P53 gene (TP53) located on chromosome 17p13. The syndrome is also associated with childhood adrenocortical carcinoma, brain tumors, osteosarcomas, and RMS [14].

The vast majority of retinoblastomas (98%) have mutations in the RB1 gene [15], and a high percentage of them (approximately 40%) show familial occurrence due to heritable mutations in the RB1 gene, which are inherited as an autosomal dominant trait and associated with a predisposition to develop other malignancies later in life [16]. Among our 4 patients with RBL there were 2 with a family history of this tumor in parents and siblings. In patients with RB1 mutations, soft tissue sarcomas and OSs are the most common SMN. This risk of their development is maximized by radiotherapy and even more by combined radio- and chemotherapy. Most tumors are located in the irradiation field. However, in our material we had 4 cases of RBL (none treated with radiotherapy) with SPTs in lower extremities (3 OS and 1 ES).

NF1 also belongs to CPS and is characterized by RAS signaling pathway dysfunction. In a Swiss paper, NF1 (and 2) constituted the largest group of CPS identified in 8074 childhood cancer patients [6]. NF1 is an interesting disease in that the spontaneous regression of tumors can occur in its course. In our material of NF1 there are 2 cases of spontaneous regression of hypothalamic tumors, most likely gliomas [17]. In our 4 patients with NF1 who were included in this study, the IT was an optic-pathway glioma, which is a WHO grade 1 pilocytic astrocytoma. One patient (No. 59) had another, hemispheric pilocytic astrocytoma, WHO 1. Two of them had 2 subsequent malignancies each; in 1 out of these 2 (No. 53), the third tumor (MPNST) was most likely secondary to the second one (RMS), in the field of irradiation. In the second one (No. 55), ependymoma in the lumbar-sacral part of the spinal canal was diagnosed. Ependymomas are associated with neurofibromatosis type 2, but in the literature case reports of ependymoma in NF1 – although very rarely – can also be found [18]. In the peripheral nervous system there is a risk of MPNST that arise in pre-existing plexiform neurofibromas, typical of this disease. RMS is the most common soft tissue sarcoma in children, and its prevalence in NF1 is about 20 times higher than that in the general population [19].

Survivors of a first SMN are at very high risk of multiple subsequent neoplasms: it is estimated that within 20 years from diagnosis of the first SMN, the cumulative incidence of a further SMN is as high as 47% [20]. In our material, 7/60 patients (11.7%) developed more than one SMN.

Special attention should be paid and care offered to patients with genetic DNA repair disorders, of which Nijmegen breakage syndrome (NBS) and ataxia-telangiectasia (AT) are the most common. Hypersensitivity to ionizing radiation, X- and γ-rays, has been demonstrated in these patients, with increased risk of lymphoid malignancy in both, and of RMS, thyroid carcinoma, gonadoblastoma, glioma, meningioma, neuroblastoma, and ES in NBS, and of breast, gastric, thyroid, liver carcinomas, and gliomas in AT [21]. Irradiation of these patients contributes to malignancies and should be avoided for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Therefore, it should be kept in mind that CT, PET/CT, and radiotherapy are contraindicated, and, as far as diagnostic imaging is concerned, US and MRI should be performed. In our material, there were no cases of these rare disorders; however, the majority of NBS patients originate from Eastern Europe and are of Slavic origin [22]. Given the influx of people, including patients from war-stricken Ukraine, it is to be expected that we will have to deal with this group of patients as well, and the need to protect them radiologically is a matter of great concern.

The study from our center by Raciborska et al. [7], among others, confirmed the possibility for the effective treatment of patients with subsequent malignant tumors; therefore, early detection and quick diagnosis are of utmost importance, as they can improve the outcome. The time of follow-up of our patients reaching up to 43.1 years confirms that.

Conclusions

Due to the risk of secondary and second (third and fourth) malignancies, life-long cancer screening is required for all childhood cancer survivors. In CPS, this risk is multiplied, as it results from both genetic factors and the treatment of previous malignancies; in these patients, multiple primary cancers must be taken into account. When assessing imaging studies of patients with a history of malignancy, clinicians should consider not only recurrence and metastases but also the possibility of a new malignancy of a different histopathological nature than the primary one.