Introduction

Acute adrenal haemorrhage (AAH) is a rare occurrence caused most commonly by an underlying adrenal tumour (of which malignant masses constitute around 20% of cases), systemic diseases (sepsis, coagulopathies, COVID), and trauma (usually in the context of multi-organ injuries) [1-3]. Due to the unique vascular structure of the adrenal glands (rich blood supply deriving from 3 main arteries and relatively poor venous drainage via single adrenal vein) sometimes described as a “vascular dam” and a tendency of platelet aggregation stimulation in cases of increased adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) secretion (predisposing to venous thrombosis and further increase of intraglandular pressure), adrenal bleeding is associated with a risk of gland insufficiency and significant morbidity and mortality [4]. Presenting symptoms of AAH include abdominal pain radiating to the flank, rigidity, and fever [5]. As far as the imaging is concerned, computed tomography (CT) with contrast injection is usually a first-choice modality in acutely unwell patients. It discloses potential underlying neoplasms, adrenal swelling, and adjacent hematomas [6]. Thorough evaluation of contrast-enhanced images in both arterial and venous phases is particularly important to detect culprit vessels and/or bleeding location [7,8]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is characterised by very high sensitivity and specificity in the characterisation of adrenal masses and determining the phase of bleeding, but its availability is limited, and it is therefore not routinely performed if AAH is suspected [9]. Ultrasound (US) with colour Doppler is preferred in the paediatric population, but its use in adult patients is limited, and US findings in AAH patients require further validation [10]. As far as the treatment of AAH is concerned, appropriate and prompt intervention is essential to avoid adrenal crisis-related mortality. Apart from adequate mineralocorticoid replacement therapy, interventional treatment aiming to stop the bleeding is required. Traditional surgical treatment was associated with very high mortality risk, and it is therefore being replaced by minimally invasive endovascular treatment in many centres world-wide [11,12].

The aim of this study is to present a multi-centre experience with endovascular treatment of AAH due to underlying neoplasms, with special attention to procedural and clinical details, as well as to provide a literature overview.

Material and methods

Study design

This is a multicentre retrospective analysis evaluating patients with AAH due to underlying neoplasms referred for emergency endovascular treatment from 2016 to 2024. The local institutional Ethical Committees approved this study, and it was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. All patients gave their informed consent for participation in the study. Inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) patients > 18 years old presenting with AAH diagnosed with CT and/or MR and confirmed in digital subtraction angiography (DSA), who underwent endovascular embolisation, 2) patients with confirmed adrenal neoplasm (primary or secondary) as an underlaying cause of bleeding, and 3) patients with haemodynamic instability and/or decrease in haemoglobin/red blood cell count. A diagnosis of active bleeding was carried out at contrast enhanced CT (slice thickness 0.6mm) in 3 phases (arterial, venous, and delayed); in each case the adrenal arteries were detected and evaluated before the intervention. Exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) other than neoplastic (iatrogenic, traumatic, spontaneous) causes of adrenal haemorrhage, and 2) patients referred for surgical treatment.

Medical records including demographics, information on adrenal neoplasm, baseline imaging and clinical details, as well as procedural outcome were collected and investigated. The complication rate was noted.

Endovascular procedure

All procedures were carried out by an experienced interventional radiologist under local anaesthesia or conscious sedation from femoral access. Firstly, an aortic angiography from a 5 Fr diagnostic catheter positioned above the renal level was performed. Afterwards, possible culprit vessels (phrenic, renal, and adrenal arteries) were selectively catheterised and investigated. If signs of vessel injury (contrast extravasation, abnormal blush) were detected superselective catheterisation with a 2.7 Fr microcatheter was performed. Embolic agents were adopted according to the type of vessel lesion and operator’s preference. Control DSA was performed to confirm vessel occlusion. The puncture site was compressed or closed with a closure device. The typical endovascular procedure is presented in Figure 1.

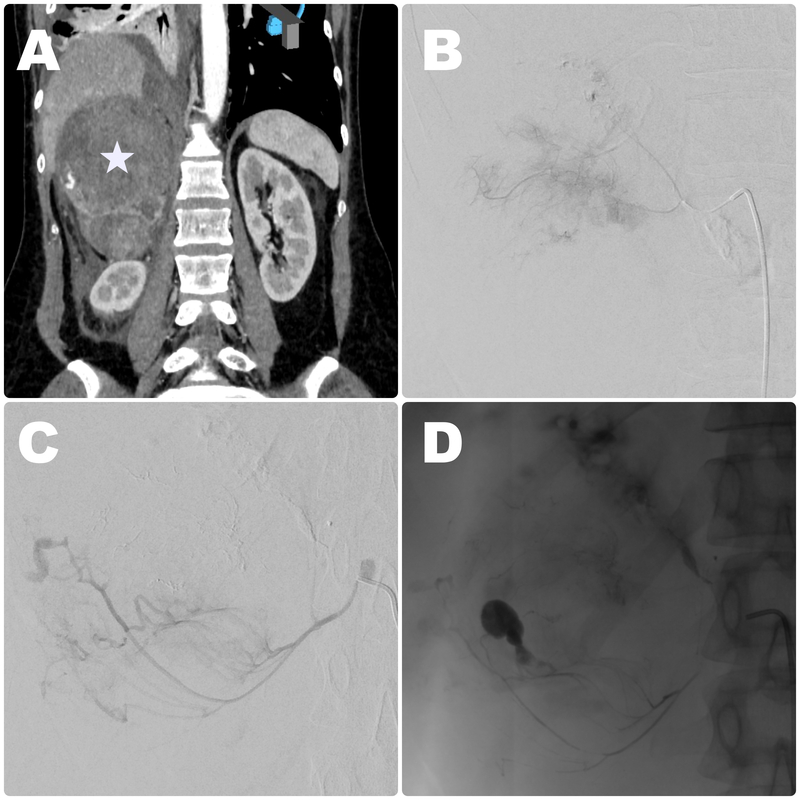

Figure 1

Embolisation procedure in a 67-year-old male patient with metastatic lesion in a right adrenal gland originating from lung cancer with signs of haemodynamic instability due to haemorrhage. A) Baseline contrast-enhanced CT disclosed large right-sided lesion in an adrenal gland (white star) with visible contrast extravasation in the lower part. Intraprocedural contrast injection showed extraluminal blush (B), and signs of contrast extravasation (C) suggestive of active bleeding from upper and middle adrenal arteries. D) Control imaging obtained after embolisation with glue showed successful exclusion of the culprit vessels

Post-operative course

All patients were monitored > 24 hours after the procedure. In addition, repeated clinical assessment and laboratory testing signs of haemorrhage and adrenal hormone excess were routinely performed. In cases of uneventful postoperative period the patients were discharged from hospital 3-7 days after the treatment. In cases of persistent haemodynamic instability or further decrease in haemoglobin, repeated CT was performed to detect possible bleeding recurrence. If bleeding was confirmed, secondary embolisation or surgical treatment was scheduled.

Results

In total, 13 patients (10 men and 3 women, mean age: 65.4 years) were included in the study. As far as the adrenal neoplasms were concerned, 8 (62%) were metastatic (5 from lung, 2 from renal, and 1 from hepatic cancers), and 5 (38%) were primary neoplasms (3 pheochromocytomas and 2 adenocarcinomas). In 9 cases (70%) the haemorrhage was right-sided, and in 4 it was left-sided. In terms of culprit vessels, in 3 patients it was the superior adrenal artery, in 4 it was the middle adrenal artery, in 2 the inferior adrenal artery, and in 4 more than one adrenal artery was diagnosed as pathological and therefore occluded during endovascular procedures. The following embolic agents were adapted: particles (in 3 cases), glue (3), coils (2), and a combination of embolic agents (5 patients). No major complications were noted. In 3 cases small, self-limiting groin haematoma at the puncture site was observed. Post-procedural haemodynamic stability was achieved in 11 patients (85%). In one patient persistent contrast extravasation in control CT was observed, and in one case no signs of bleeding were observed. The first patient was referred for surgical treatment (adrenalectomy), and the second was treated conservatively. Clinical and procedural details are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Clinical and procedural details of the treated patients

Discussion

AAH is an uncommon disorder with diverse aetiology, uncharacteristic clinical presentation, and variable prognosis, which requires early diagnosis and prompt treatment [13]. Because high-quality data on the management standards of AAH are lacking, the aim of our report is to present our multicentre experience of these patients and secondary adrenal haemorrhage treated endovascularly.

Adrenal lesions present a broad spectrum of conditions, extending from benign (adenomas, pheochromocytomas) to malignant tumour involvements [14]. Additionally, adrenal glands are a common site for metastasis from other primary tumours, originating most frequently from lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, melanoma, breast, and gastrointestinal cancer [15]. Adrenal metastasis portends a grim prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of 20-25%, frequent recurrences, and limited treatment options [16]. Due to its rich vasculature, potential haemorrhage from adrenal lesions is associated with high risk of gland insufficiency and significant morbidity and mortality [4]. That is why adrenal artery embolisation might be performed in elective cases of oncological patients for both palliative (pain and tumour bulk reduction) and preoperative (reduction of tumour vascularity) purposes [17]. Emergency embolisation, on the other hand, is performed for haemostasis of retroperitoneal haemorrhage [12]. In our experience, endovascular embolisation for bleeding adrenal lesions was associated with high rate of clinical success, defined as haemodynamic stability following the procedure – it was achieved in 85%, which is comparable with results reported by other authors [12,18]. It appears that neither the nature of the lesion (primary vs. secondary) nor the primary tumour location and type influence the outcome. In addition to that, apart from minor complications at the puncture site, no procedural complications were noted. As far as the technical aspects of the endovascular procedures were concerned, our study confirms the observation made by the above-mentioned authors with regard to the importance of pre-operative imaging examination in the detection of culprit vessels. In our experience, all 3 adrenal arteries may be a source of bleeding, and in some cases occlusion of more than one vessel is necessary.

Our study presents several limitations. First and foremost, this is a retrospective analysis, and therefore bias selections should be considered. Secondly, the sample group is relatively small; however, considering the overall prevalence of AAH, especially caused by underlying malignancy, this should not be perceived as a drawback. Finally, our study lacks a control arm including patients treated with surgical methods. Nonetheless, endovascular therapy has become a first-line therapy in AAH in our centres, which is why data of patients treated differently are lacking.