Introduction

Neck pain syndromes with proximal upper extremity motor deficit have an age-standardized prevalence of 27.0 per 1000 population of patients with peripheral nervous system (PNS) disorders [1]. It can be manifested by disc protrusion, thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS), compression of nerve structures by tumour infiltration, injury, infectious diseases, and autoimmune disorders [2]. Such a wide range of aetiopathological conditions poses a significant challenge to clinicians. Therefore, it is necessary to perform efficient diagnostic procedures in these patients, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), nerve conduction studies (NCS), ultrasound imaging, and immunologic testing [3,4].

In recent years, ultrasound imaging of the PNS has improved significantly. This has been made possible by the introduction of high-resolution ultrasound (HRUS), which uses probes with a centre frequency of ultrasound > 15 MHz, which is higher than that used in traditional linear transducers, which routinely operate between 2 and 15 MHz. The high-resolution images produced by the high-frequency beams make it possible to visualise not only the major nerve trunks and minor branches of the brachial plexus, but also damage to individual nerve bundles, such as swelling of the anterior interosseous nerve bundles within the median nerve trunk [5].

The use of HRUS can significantly aid in the diagnosis of brachial plexus pathologies, as early manifest radiologic signs precede the onset of less characteristic clinical symptoms. In Parsonage-Turner syndrome (PTS), an idiopathic plexopathy is caused by an inflammatory process within the individual branches of the brachial plexus, leading to swelling of the nerve structures, and HRUS shows primarily thickening of the myelin sheath and secondary twisting of the nerve in the form of an “hourglass-like” constriction [6]. Because the clinical manifestations of PTS can be similar to Banwarth’s syndrome caused by Borrelia infection, HRUS can provide key data to guide further diagnosis and implementation of appropriate targeted therapy for each disease and further individualized rehabilitation [7,8].

In the following manuscript, we present a proposed HRUS protocol and clinical examples of ultrasound evaluation of the brachial plexus in patients with PTS and neuroborreliosis.

Brachial plexus HRUS protocol

Major clinical pathologies of the brachial plexus may manifest as a similar neurological syndrome. Therefore, a reproducible examination scheme is required for accurate evaluation of the brachial plexus. The proposed HRUS protocol for brachial plexus evaluation is shown schematically in Table 1. It focuses on the rapid detection of key pathologies that may be the underlying cause of upper extremity paresis and pain. It includes evaluation of the C5-C7 roots at the point of exit between the transverse processes of the cervical spine and between the scalene muscles with measurement of the cross-sectional area (CSA) (Table 1A). Once the roots have been assessed, the upper trunk formed by the C5 and C6 roots (Table 1B) is a good landmark to examine in case of structural changes of the scalene triangle, e.g. post-traumatic. This is the point of examination when the C7 root also enters the middle trunk and the C8 and Th1 roots form the lower trunk. In the supraclavicular fossa, the entire area is evaluated with HRUS (Table 1C). Assessment of the major components of the brachial plexus is followed by identification and examination of the short branches. The long thoracic nerve is assessed within the middle scalene muscle and is best seen at the level of the C6 nerve root (Table 1D). The suprascapular nerve is then assessed along its course from the upper trunk (UT) to the scapular notch (Table 1E). Evaluation of the axillary nerve in this protocol includes visualisation of its anterior and posterior projections. The probe should be placed under the coracoid process and then rotated obliquely to locate the coracobrachialis muscle. The circumflex humeral artery and associated axillary nerve are visible at its edge (Table 1F). This projection provides the opportunity to visualise a CSA of the axillary nerve behind its bifurcation from the posterior bundle. A posterior projection can be obtained by positioning the transducer vertically within the posterior surface of the shoulder muscle to visualise the quadrangular space along with the axillary nerve and the posterior circumflex humeral artery that emerge from it, which, as with the anterior projection, provides a good reference point for determining the anatomical relationships between the structures being examined (Table 1G). The axillary fossa with evaluation of the medial, lateral, and posterior cords is the final stage of the brachial plexus HRUS protocol (Table 1H). The table lists examples of pathologies observed at appropriate levels of ultrasound examination of the plexus. It is important to identify not only individual lesions, but also their distribution and mutual coexistence within the brachial plexus, which determines the different clinical approach to numerous neurological disorders, including: typical and focal forms of CIDP (chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy), conduction block at the level of the plexus in MMN (multifocal motor neuropathy), PTS, infectious brachial neuritis, and TOS (Table 2) [9].

Table 2

Schematic overview of possible ultrasound findings in selected neurological disorders

Parsonage-Turner syndrome

PTS or neuralgic amyotrophy (NA) is an idiopathic inflammation of the brachial plexus. PTS is a rare disease with an estimated incidence of 1.64 per 100,000 people per year [8]. It affects men more often than women and presents more frequently in the third and seventh decades of life. There are 2 different forms of NA: idiopathic and hereditary. The aetiology of the idiopathic form and the pathophysiology of this syndrome are not fully understood. In the literature there are cases of idiopathic PTS associated with viral infection, vaccination, surgery, trauma, and autoimmune diseases, all of which may involve disruption of the natural blood-epineural barrier [10-15]. Susceptibility of the brachial plexus to trauma is also considered as a possible pathophysiological background of the syndrome, due to the aforementioned mechanism of blood-epineural barrier damage [16]. The hereditary form of NA is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern and tends to be recurrent. It is associated with abnormal expression of genes encoding the septin protein, of which the septin 9 mutation on chromosome 17 is a confirmed mutation in families with the hereditary form of the disease [17].

Symptoms usually begin with acute, unilateral, piercing shoulder pain. The pain subsides within a few weeks, leaving a loss of sensory and motor symptoms. Eventually, there is atrophy of the muscles innervated by the affected nerves in the shoulder girdle and proximal part of the upper extremity [10-13]. However, the distribution of nerve involvement and the degree and type of damage in PTS can be very heterogeneous. This may be reflected in both NCS and HRUS. Any nerve may be involved in the pathological process in neuralgic amyotrophy, but the upper trunk of the brachial plexus is most commonly affected. The nerves that are typically involved are as follows: the long thoracic nerve, the phrenic nerve, the suprascapular nerve, the musculocutaneous nerve, the axillary nerve, the anterior interosseous nerve (AIN), and the deep branch of the radial nerve – the posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) [11,12,14].

Until recently, the diagnosis of PTS was mainly based on history, physical examination, and characteristic clinical features [12,13]. For years, only NCS remained the main ancillary test. Diagnostic imaging with magnetic resonance mostly aimed at the exclusion of other causes that could produce a similar clinical picture, such as rotator cuff pathology, cervical discopathy, or malignancy. It also still serves as a “gold standard” for muscles atrophy assessment [1-14]. Conversely, HRUS may provide a pathognomonic sign of PTS – a torsion of the nerve, which on imaging takes the form of an “hourglass-like” constriction visible in the long axis of the nerve [6,11] (Figures 1 and 2). Thickening, swelling of the nerve with obliteration of its echogenic structure, and twisting and swelling of the bundles within the nerve trunks are the other features of the pathological process in the course of PTS that should be looked for on ultrasound imaging [10,18]. HRUS examination of the brachial plexus can also indicate the autoimmune background of PTS by showing swelling of the roots and nerve trunks, which is common in inflammatory injury (Figure 3). HRUS can also visualise the severity of muscle atrophy secondary to motor denervation (Figure 4).

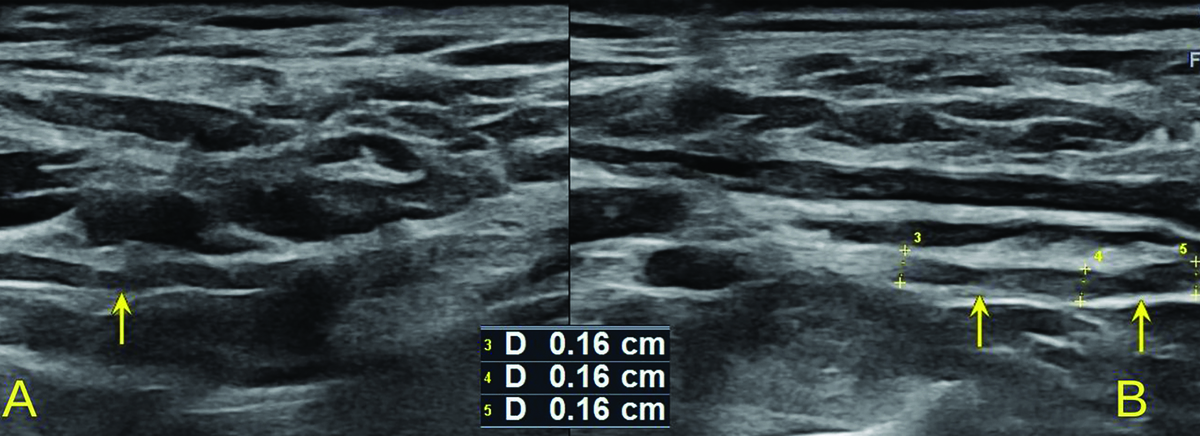

Figure 1

High-resolution ultrasound image of the suprascapular nerve torsion with a double “hourglass-like” constriction sign – marked with arrows (B) in 57-year-old patient with Parsonage-Turner syndrome in comparison with asymptomatic side (A). Images obtained by author with a 3-19 H linear probe of the Alpinion XCube90

Figure 2

High-resolution ultrasound image of LTN torsion with an ”hourglass-like” constriction sign – marked with arrow (A) with comparison to the asymptomatic side (B) in 50-year-old patient with Parsonage-Turner syndrome. Images obtained by author with a 3-19 H linear probe of the Alpinion XCube90

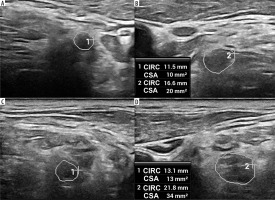

Figure 3

High-resolution ultrasound image of the C5 (A, B) and C6 (C, D) roots with cross sectional area (CSA) measurements in 57-year-old patient with Parsonage-Turner syndrome. Root swelling, reflected by increased CSA and circumference (CIRC) detected on the symptomatic side. Images obtained by author with a 5-20 MHz linear probe of the Mindray Resona I9

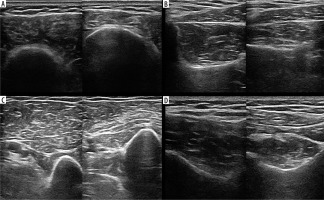

Figure 4

High-resolution ultrasound image of atrophy of the deltoid (A), biceps brachii (B), supraspinatus (C) and infraspinatus (D) muscles in a 57-year-old patient with Parsonage-Turner syndrome – right side of each section. Images obtained by author with a 5-20 MHz linear probe of the Mindray Resona I9

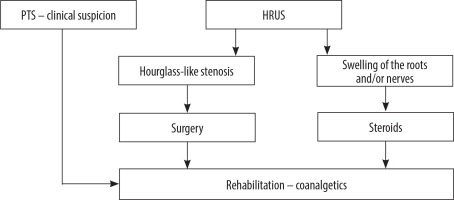

Treatment of PTS is not yet part of the gold standard of care, but there is evidence of good clinical practice. Given the probable autoimmune background of the disease, steroid therapy is recommended, especially in the acute phase of the disease. The addition of opioids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may support prednisone treatment [8]. Antiepileptic drugs such as gabapentin and pregabalin are effective adjunctive treatments for neuropathic pain, but their usefulness in the acute phase of the disease is limited because of their delayed onset [14]. A holistic approach to the patient with NA remains essential, including rehabilitation of motor deficits in addition to pharmacological treatment. This should focus on restoring joint range of motion and preventing the development of further muscle wasting [8,13,14]. Surgical treatment is also not yet standard practice. In some treatment-resistant cases, surgical decompression of the nerves involved in the disease process may be indicated, but the appropriate time for surgical treatment should be carefully considered on a patient-by-patient basis [13,14]. It is believed that PTS cases with persistent nerve torsion in the absence of clinical response to conservative treatment may be candidates for surgical decompression (Figure 5). Depending on the degree of torsion of the affected nerve, the procedure may be minimally invasive, involving intrafascicular neurolysis or nerve grafting [19]. HRUS can provide accurate follow-up assessment of twisted nerves. By detecting persistent nerve damage or complete nerve recovery, it can guide further rehabilitation or determine the need for surgical re-treatment.

Neuroborreliosis and Banwarth syndrome

Lyme borreliosis is the most common tick-borne infectious disease in Europe. Infection occurs through the bite of an Ixodes ricinus tick, which carries spirochetes of Borrelia species [20,21]. Of the known Borrelia species, B. burgdorferi, B. afzelii, B. bavariensis, B. garinii, and B. spielmanii have the greatest infectious potential, with a proportional prevalence in different regions of the world [20]. The clinical picture of the disease varies depending on the stage of infection. The history of the tick bite and the presence of erythema migrants, which indicates the acute phase of the disease, remains an important element in the diagnosis of neuroborreliosis. It is believed that further progression of infection and systemic reaction may occur several weeks to several months after the tick bite. The clinical picture may then take the form of generalised musculoskeletal pain with concurrent subfebrile states. Approximately 3-15% of infected individuals develop nervous system involvement and a wide range of neurological clinical manifestations [20]. The most common is lymphocytic meningitis with spinal nerve root involvement and cranial nerve damage, i.e. Banwarth syndrome [12,20]. Of the cranial nerves, the facial nerve is most commonly affected, but it should be remembered that almost any cranial nerve (except the olfactory nerve) can be affected in the course of neuroborreliosis [20].

Along with meningitis, spinal nerve root inflammation is a common neurological manifestation of neuroborreliosis. It manifests as segmental neuropathic pain that often awakens patients at night, sometimes progressing over time to limb paralysis [20]. Other clinically important forms of neuroborreliosis include polyneuropathy, mononeuropathy, and inflammation of peripheral nerves, including the brachial and lumbosacral plexuses [2,12,21]. Interestingly, brachial plexitis secondary to Borrelia infection remains an intriguing clinical observation of a specific overlap between full-blown PTS and neuroborreliosis. The interpenetration of these 2 disease entities poses a significant challenge to clinicians. Therefore, the search for Borrelia spirochetes infection as one of the causes of PTS is increasingly discussed as a potential standard of care in determining the aetiology of PTS [22,23].

The key to diagnosing this infectious disease is testing serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for the presence of antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi. The presence of antibodies in the CSF with clinical correlation indicates the need for intravenous antibiotic treatment [7]. The predilection of the disease process to occupy the proximal structures of the peripheral nervous system presents diagnostic difficulties because this area is often excluded from a complete examination of the NCS. Methods of structural imaging of the brachial plexus and upper extremity peripheral nerves, including HRUS, may be helpful in this situation.

HRUS of the brachial plexus, which, when combined with a complete ultrasound examination of the nerve structures of the upper extremity and a complementary NCS examination, provides a complete spectrum of structural and functional diagnosis of the peripheral nervous system. The most common ultrasound-detected lesion of the brachial plexus in brachial neuritis of infectious origin is multiple swellings of individual nerves and roots (Figures 6 and 7). In the case of Banwarth syndrome, using HRUS, generalised thickening and swelling not only of the roots but of the entire nerve, characteristic of this syndrome, can be observed (Figure 8). It is also possible to visualise nerve thickening with high-resolution ultrasound probes in the case of facial nerve damage in Banwarth syndrome (Figure 9).

Figure 6

High-resolution ultrasound (HRUS) image of the C5 (A, B) and C6 (C, D) roots and upper trunk (UT) (E, F) in 66-year-old patient with the left upper limb paresis due to neuroborreliosis with Banwarth syndrome. Side-by-side comparison with increased measurements on the symptomatic side. Images obtained by author with a 5-20 MHz linear probe of the Mindray Resona I9

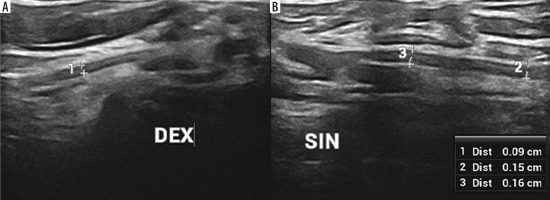

Figure 7

High-resolution ultrasound (HRUS) image of the suprascapular nerve (DEX – asymptomatic side, SIN – symptomatic side) with measurements in brachial neuritis due to neuroborreliosis. Side-by-side comparison. Images obtained by author with a 5-20 MHz linear probe of the Mindray Resona I9

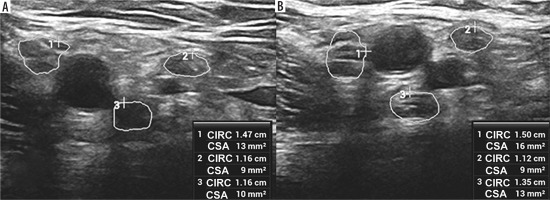

Figure 8

High-resolution ultrasound (HRUS) image of the brachial plexus in the region of the axilla with increased measurements of the lateral (1), medial (2) and posterior (3) cords of the symptomatic side in brachial neuritis due to neuroborreliosis with Banwarth syndrome. Images obtained by author with a 5-20 MHz linear probe of the Mindray Resona I9

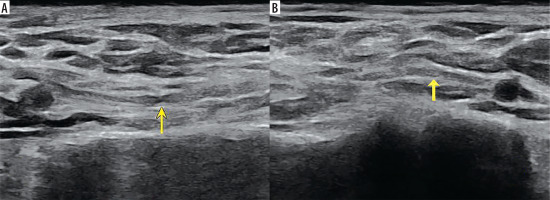

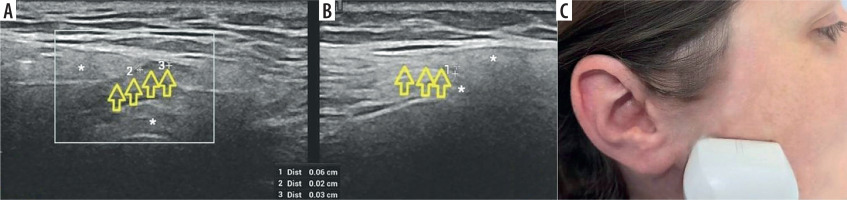

Figure 9

High-resolution ultrasound (HRUS) image of the facial nerve – marked with arrows within the parotid gland. Asymptomatic side (A) in comparison with thickening and blurring of echogenicity on the affected side (B) in 73-year-old patient with facial nerve palsy due to neuroborreliosis. Probe placement is at a height of approximately one-half of the ramus of the mandible, above the parotid gland (C). Images obtained by author with a 5-20 MHz linear probe of the Mindray Resona I9

Discussion

Parsonage-Turner syndrome is still frequently misdiagnosed with other disorders of the shoulder girdle and cervical spine. It may also be caused by and overlap with neuroborreliosis, one of the most common infectious diseases, with numerous clinical manifestations affecting both the peripheral and central nervous systems. In addition, compression of the roots and nerves of the brachial plexus in the interscalene triangle may resemble the above conditions. The heterogeneous picture of PTS in terms of damage to neural structures may cause difficulties in the selection of diagnostic methods and further effective and targeted treatment. The similarity in the distribution of nerve damage and the initial course of the above-mentioned diseases allows them to mimic each other perfectly. Therefore, the path to a definitive diagnosis can sometimes be challenging.

The use of HRUS can significantly assist in the identification of the problematic nature of neuropathic pain and paresis in the upper extremities. Complex HRUS examination of the interscalene triangle area in differential diagnosis allows precise determination of the type and extent of damage to neural structures in each of the above syndromes. As a result, an ultrasound examination can facilitate the precise management of PTS and neuroborreliosis according to their characteristic radiologic features.

Therefore, a standardised, schematic approach to the examination of the brachial plexus in any patient with flaccid upper limb paresis and complaints of shoulder or neck pain is proposed. In our opinion, a structured, point-by-point ultrasound evaluation of the brachial plexus for radiologic evidence of damage can be very helpful in differentiating conditions such as PTS and neuroborreliosis. It should be noted that ultrasound has a number of limitations, the most important of which remain the skill and experience of the examiner and the limitations of the equipment, particularly relevant in the case of HRUS. In fact, only centres specialised in neuromuscular ultrasound are able to gain enough experience to accurately interpret the results and measurements obtained. However, by popularising the use of even simplified examination schemes, it is possible to sensitise clinicians and radiologists to the often-underdiagnosed problem of brachial plexus disorders. Nevertheless, the additional use of contrast-enhanced MRI, which has been shown to be a valuable and sensitive tool for evaluating brachial plexus injuries, may be necessary to make a definitive diagnosis or to confirm ultrasound findings [24].

Thus, we believe that the HRUS protocol proposed in this publication provides a verifiable, comprehensive assessment of key elements of the brachial plexus. The non-invasive nature of the test and the fact that it can be performed and repeated frequently at the patient’s bedside greatly enhance its applicability. It is also possible to compare the same examination in different patients, sometimes with a similar clinical picture, and in the presence of radiological differences, it provides the opportunity for rapid differential diagnosis of a wide variety of brachial plexus deficits.