Introduction

Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) is an X-ray-based imaging method with a shorter scanning time and lower radiation dose than traditional CT [1,2]. This system is commonly used in dental practice to provide three-dimensional high-resolution visualization of the structure of oral and maxillofacial lesions, helping the diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in the patients efficiently [3,4]. However, different factors can negatively influence the interpretation accuracy of the prepared scans, such as low inter- and intra-observer agreement (principally for junior and less experienced practitioners) [5,6]; therefore, CBCT imaging has weaknesses as well as the advantages mentioned above.

Artificial intelligence is a wide-ranging branch of computer science (software-based) that enables machines to learn and simulate human behaviour automatically. This system has been suggested in recent years as a supplementary tool to potentially increase the diagnostic performance of other imaging instruments in dental practice, such as CBCT [7,8].

Several studies have assessed the diagnostic performance of artificial intelligence integrated with CBCT imaging in relation to oral and maxillofacial anatomical landmarks and lesions. In this regard, the researchers have reported differing values of accuracy [9-11]. However, no comprehensive studies have endeavoured to resolve these conflicting data. Therefore, in the present study, we aimed to conduct a contemporaneous systematic review and meta-analysis of studies reporting the accuracy of artificial intelligence in the detection and segmentation of oral and maxillofacial structures, with a focus on CBCT images, to provide an overall estimate for the diagnostic performance of artificial intelligence.

Material and methods

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

We reported the present study based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline [12]. We did a literature search of the Embase, PubMed, and Scopus databases for reports published from their inception to 31 October 2022 without language restrictions using the following keywords: artificial intelligence OR deep learning OR machine learning OR automatic OR automated AND cone-beam computed tomography OR CBCT. The search was limited to the Title/Abstract. We enrolled original research publications that explored the accuracy of artificial intelligence in the automatic detection or segmentation of oral and maxillofacial anatomical landmarks or lesions using CBCT images. Accuracy referred to the rate of correct findings regarding all the findings observed. We excluded reviews, case reports, editorials, and letter to the editors. We also excluded duplicate publications. Reports without extractable data on the study outcome were also excluded. Finally, studies not published in full text were ineligible for inclusion. We performed a hand search of the references of the retrieved articles to capture additional papers.

Study selection and data extraction

We independently investigated the eligibility of the sources primarily identified in the database search by screening the titles and abstracts using a pre-designed suitability form. In the next step, we collected the full texts of the relevant reports for more detailed appraisals. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus between the reviewers. We extracted the following data from the eligible studies finally selected for inclusion: first author’s name, publication year, study location (country), objective, study design, artificial intelligence technique, validation method, sample size, and accuracy value (ranging from 0.00 to 1.00). If a study used different artificial intelligence techniques or validation methods, we considered each as a separate report. We used Google Translate for translating full texts not in English.

Statistical analysis

We pooled the accuracy values of artificial intelligence extracted from the studies using a random-effects model to provide overall estimates. We also performed subgroup analysis according to anatomical landmarks/lesions, detection/segmentation tasks, and artificial intelligence technique. The estimates calculated were presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We used the I2 index to explore the heterogeneity between the studies, which ranges from 0.0% to 100.0%; a p-value < 0.10 was considered statistically significant [13]. Forest plots were generated to illustrate the results of the meta-analysis. We appraised the publication bias using a funnel plot. We also conducted a meta-regression to assess the potential influence of the publication year on the study outcome, and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant; a scatter plot was drawn in this regard. All statistical analyses were carried out by Comprehensive Meta-Analysis V2 software.

Results

Search results and study selection

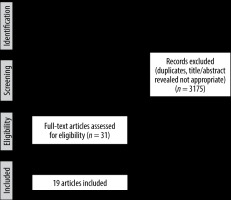

A total of 3206 records were yielded from the initial electronic database search, of which 3175 papers were excluded because of either duplication or unsuitability. Full texts of the remaining 31 articles were then evaluated. Ultimately, 19 studies were identified as eligible for inclusion in this systematic review and meta-analysis [9-11,14-29]. The PRISMA flowchart of the search strategy and results is presented in Figure 1.

Study characteristics

Out of 19 individual studies included in this review, there were 4 studies from China, 4 studies from Iran, 3 studies from Belgium, 2 studies from Turkey, one study from Austria, one study from South Korea, one study from Thailand, one study from the USA, and 2 multicentre studies. The language of all articles was English. The publication year of the studies was between 2017 and 2022. Deep learning was the most frequently used artificial intelligence technique in the studies. Table 1 summarizes the baseline information of the included surveys.

Table 1

Baseline characteristics of the included studies

| Study | Country | Objective | Study design | Artificial intelligence technique | Validation method | Sample size (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdolali, 2017 [14] | Iran | Classification of maxillofacial cysts | Development | Support vector machine and sparse discriminant analysis | Three-fold cross-validation | 125 scans (20,000 axial images) | ||

| Abdolali, 2019 | Iran, | Maxillofacial lesion | Development | Knowledge-based support vector | Split-sample | 1145 scans | ||

| [15] | Japan | detection | machine and sparse discriminant analysis | validation | ||||

| Chai, 2021 | China | Ameloblastoma | Development | Deep learning | Split-sample | 350 scans | ||

| [16] | and odontogenic | (convolutional neural network) | validation | |||||

| keratocyst diagnosis | ||||||||

| Fontenele, 2022 | Belgium | Tooth segmentation | Validation | Deep learning | Split-sample | 175 scans | ||

| [9] | (convolutional neural network) | validation | (500 teeth) | |||||

| Gerhardt, 2022 | Belgium | Detection and labelling | Validation | Deep learning | Split-sample | 175 scans | ||

| [10] | of teeth and small | (convolutional neural network) | validation | |||||

| edentulous regions | ||||||||

| Haghnegahdar, | Iran | Diagnosis of | Development | K-nearest neighbour | Ten-fold | 132 scans, 66 patients | ||

| 2018 | temporomandibular | cross-validation | (132 joints) with TMD | |||||

| [17] | joint disorders | and 66 normal cases | ||||||

| (132 joints) | ||||||||

| Hu, 2022 | China | Diagnosis of vertical | Validation | Deep learning | Five-fold | 552 tooth images | ||

| [18] | root fracture | (con | volutional neural network | cross-validation | ||||

| [ResNet | -50, VGG-19, DenseNet-169]) | |||||||

| Johari, 2017 | Iran | Detection of vertical | Development | Probabilistic neural network | Three-fold | 240 radiographs of extrac- | ||

| [11] | root fractures | cross-validation | ted teeth (CBCT and PA), | |||||

| 120 intact, 120 fractured | ||||||||

| Kirnbauer, 2022 | Austria | Detection of periapical | Development | Deep learning (convolutional neural | Four-fold | 144 scans | ||

| [19] | osteolytic lesions | and validation | network [SpatialConfiguration-Net]) | cross-validation | ||||

| Kwak, 2020 | China, | Segmentation of | Development | Deep learning | Split-sample | 102 scans | ||

| [20] | Finland, | mandibular canal | (convolutional neural network [U-net]) | validation | (49,094 images) | |||

| South | ||||||||

| Korea | ||||||||

| Lahoud, 2022 | Belgium | Mandibular canal | Development | Deep learning | Split-sample | 235 scans | ||

| [21] | segmentation | and validation | validation | |||||

| Lee, 2020 | South | Detection and diagnosis | Development | Deep learning | Split-sample | 2126 images | ||

| [22] | Korea | of odontogenic kerato- | (convolutional neural network) | validation | (1140 panoramic | |||

| cysts, dentigerous cysts, | and 986 CBCT images) | |||||||

| and periapical cysts | ||||||||

| Lin, 2021 | China | Pulp cavity and tooth | Validation | Deep learning | External | 30 teeth | ||

| [23] | segmentation | (convolutional neural network [U-net]) | validation | |||||

| Roongruangsilp, | Thailand | Dental implant | Development | Deep learning (region-based | Split-sample | 184 scans | ||

| 2021 [24] | planning | convolutional neural network) | validation | |||||

| Serindere, 2022 | Turkey | Diagnose of maxillary | Development | Deep learning | Five-fold cross- | 296 images | ||

| [25] | sinusitis | (convolutional neural network) | validation | |||||

| Setzer, 2020 | USA | Periapical lesions | Development | Deep learning | Five-fold cross- | 20 volumes (61 roots) | ||

| [26] | detection | (convolutional neural network) | validation | |||||

| Sorkhabi, 2019 [27] | Iran | Alveolar bone density classification | Development | Deep learning (convolutional neural network) | Split-sample validation | 83 scans (207 surgery target areas) | ||

| Wang, 2021 [28] | China | Segmentation of oral lesion | Validation | Deep learning (convolutional neural network) | External validation | 90 scans | ||

| Yilmaz, 2017 [29] | Turkey | Diagnosis of the periapical cyst and keratocystic odontogenic tumour | Development | Support vector machine | Ten-fold cross-validation, split-sample validation, leave-one-out cross validation | 50 dental scans | ||

Overall accuracy

Nineteen individual studies reported the diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence using oral and maxillofacial CBCT images. The lowest and highest accuracy values reported were 0.78 and 1.00, respectively. Analysis of the studies showed that the overall pooled diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence was 0.93 (95% CI: 0.91-0.94; I2 = 93.3%, p < 0.001) (Figure 2). The funnel plot was suggestive of publication bias (Figure 3). Meta-regression analysis revealed that the publication year explained the heterogeneity for the outcome (β = –0.137, p = 0.045) (Figure 4).

Figure 2

Diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence using oral and maxillofacial cone-beam computed tomography imaging

Accuracy by anatomical landmarks and lesions

There were 7 individual studies that reported the dia-gnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence for oral and maxillofacial anatomical landmarks using CBCT images. Analysis of these studies demonstrated that the pooled diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence was 0.93 (95% CI: 0.89-0.96; I2 = 90.3%, p < 0.001) for anatomical landmarks. In addition, the diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence for oral and maxillofacial lesions was investigated in 12 studies. According to the analysis of these studies, the overall pooled diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence was 0.92 (95% CI: 0.90-0.94; I2 = 95.1%, p < 0.001) for lesions. Figure 5 visualizes the results of the subgroup analysis by anatomical landmarks and lesions.

Accuracy of detection and segmentation

Figure 6 displays the forest plot of the pooled accuracy of artificial intelligence in detecting and segmenting oral and maxillofacial structures using CBCT images. Analysis of 14 studies reporting the information on the detection accuracy indicated that the pooled accuracy of detection for artificial intelligence was 0.93 (95% CI: 0.91-0.94; I2 = 94.7%, p < 0.001). Also, based on the analysis of 5 studies that assessed the segmentation accuracy of artificial intelligence using the CBCT system, the overall pooled accuracy of segmentation for artificial intelligence was 0.92 (95% CI: 0.85-0.95; I2 = 91.9%, p < 0.001).

Accuracy by artificial intelligence technique

Fifteen studies reported the artificial intelligence accuracy using the deep learning techniques [9-11,16,18-28], and 4 studies reported the accuracy using machine learning [14,15,17,29]. According to the analysis, the pooled diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence was 0.93 (95% CI: 0.90-0.95; I2 = 92.7%, p < 0.001) using deep learning and 0.93 (95% CI: 0.89-0.96; I2 = 94.6%, p < 0.001) using machine learning.

Discussion

Artificial intelligence systems are presently utilized as auxiliary equipment for clinical and paraclinical management of dentomaxillofacial conditions due to recent technological developments in computer-aided tools [30,31]. However, the validity and reliability of these applications remained to be determined. To answer this question, several studies tried to investigate the diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence regarding oral and maxillofacial structures with a focus on CBCT imaging; however, the reported values varied between the surveys [8,19-23], needing a comprehensive study to gather the available data and calculate an overall estimate on this topic. In the current systematic review and meta-analysis, we assembled information from 19 studies that reported the values of artificial intelligence accuracy in the detection and segmentation of oral and maxillofacial structures using CBCT scans. We found that the overall pooled diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence was 0.93, which is an excellent performance. Moreover, recent publications demonstrated lower accuracy values. The accuracy value interestingly remained high when we performed subgroup analysis by anatomical landmarks and lesions; i.e. the pooled diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence was 0.93 for anatomical landmarks and 0.92 for lesions. Also, other subgroup analyses indicated that the pooled accuracy values of detection and segmentation were 0.93 and 0.92, respectively.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis that comprehensively assessed the available evidence in the literature on the detection and segmentation accuracy of artificial intelligence models about oral and maxillofacial structures using CBCT images. Preview reviews either did not conduct a meta-analysis [32] or included very few studies [33]. In the present study, we systematically searched multiple databases with different keywords. Then we screened thousands of citations initially identified using strict eligibility criteria. We used a random-effects model for pooling the data to provide more conservative estimates. We also evaluated the publication bias using a funnel plot. In addition, meta-regression analysis was performed to explore the influence of publication year on the study outcome. Finally, we conducted subgroup analyses to minimize the effect of heterogeneity on the study findings.

As per the available evidence, clinicians utilize artificial intelligence systems in different oral and maxillofacial fields, typically such as orthodontics, endodontics, implantology, and oral and maxillofacial surgery [31,32]. Concerning orthodontics, researchers proposed that deep learning frameworks could be used in automatic landmark detection and cluster-based segmentation about cephalometric analysis [34,35]. With respect to endodontics, studies suggested learning models for detecting and segmenting tooth roots, alveolar bone, and periapical lesions, using methods that incorporate knowledge of orofacial anatomy, resulting in fewer images for training [7,11,26]. Regarding dental implant planning, region-based and three-dimensional deep convolutional neural network algorithms have been developed for qualitative and quantitative appraisal of alveolar bone, with acceptable diagnostic performance [24,27,36]. Pertaining to oral and maxillofacial surgery, deep learning has been utilized for diagnosing and classifying temporomandibular joint diseases, maxillary and mandibular segmentation, and guiding oral and maxillofacial surgeons with high diagnostic performance [16,17,23]. The studies included in our review assessed different anatomical regions, such as maxillary sinuses, temporomandibular joint, dental roots, dental alveoli, periodontium, pulp cavity, and mandibular canal. Furthermore, various artificial intelligence techniques were used in the studies, but deep learning was the most common among them.

A weakness of the present review study was the high heterogeneity between the retrieved surveys, which could be explained by differences in study location, purposes, sample size, scanning device and parameters, presence of noise or artifacts, image acquisition protocols, and interobserver or intraobserver agreement. It should be mentioned that publication bias could justify the heterogeneity for the study outcome. Also, the publication year explained the heterogeneity in the outcome according to the meta-regression results. Altogether, it is proposed that more homogeneous research be designed and carried out.

Conclusions

The results of this systematic review and meta-analysis revealed excellent accuracy for the detection and segmentation tasks of artificial intelligence systems using oral and maxillofacial CBCT images. Artificial intelligence-based systems seem to have the potential to streamline oral and dental healthcare services and facilitate preventive and personalized dentistry. Positive and negative points and challenges of these applications need to be evaluated in further clinical studies.