Introduction

An increase in accessibility and frequency of using imaging techniques to visualise the abdominal cavity, especially ultrasonography (USG), have in recent years resulted in the higher detection rate of so-called “incidentalomas”, i.e. focal liver lesions (FLL), both solitary and multiple [1,2]. FLL are common; based upon imaging results, its incidence is estimated at between 5 and 18%, while based on autopsies – as much as 20% [3]. Most FLL are benign, and the most common findings involve focal fatty sparing, followed by cysts and adenomas [1,3]. Such lesions do not require biopsy, treatment, or follow-up. An attentive diagnostic process is crucial because the incidence of malignant lesions, including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), is increasing [4]. Early detection of these neoplasms enables proper treatment and is associated with a higher likelihood of the therapy’s success. The probability of the malignancy can be initially assessed based on the interview and examination of the patient, during which features like cirrhosis, chronic liver disease, unintentional weight loss, fever, or night sweats should be noted [3]. Depending on the clinical context, assessment of tumour markers such as alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), or antigen CA 19-9 might be helpful in determining the character of FLL [3].

Imaging accompanied by clinical presentation and biochemistry results lead in most cases to a precise diagnosis. According to some experts, FLL discovered in USG in non-cirrhotic liver should be primarily verified by contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS). In the case of problems with accessibility of CEUS, lesions should be visualised in contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MRI) (depending on the lesion size) [3].

Liver biopsy

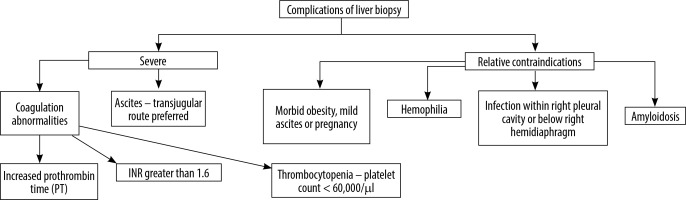

If imaging results are inconclusive, percutaneous liver biopsy should be considered [4]. There are several indications for the procedure (Table 1). In certain clinical situations (Figure 1) [5] performing liver biopsy is associated with increased risk, but most of these contraindications are relative. The decision of performing biopsy should be thoroughly considered because this diagnostic tool is burdened by complications - the most frequently mentioned are pain, bleeding (0.12-1.6%), dissemination of neoplastic cells (0.76-1.6%), peritonitis, and trauma of intestines or lung [6].

Table 1

Indications for liver biopsy

In 2015 the European Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology (EFSUMB) prepared recommendations concerning liver biopsy (Table 2). Although the level of these recommendations is strong or moderate, evidence is rather weak [5]. In 2020 the British Society of Gastroenterology in cooperation with the Royal College of Radiologists and the Royal Collage of Pathology published their own counselling, which was coherent with cited European guidelines.

Table 2

Recommendations of European Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology (EFSUMB)

[i] Levels of evidence and grades of recommendations are assigned in concordance with the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine criteria (2009 edition) – http://www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009

Imaging-guided liver biopsy

According to the mentioned recommendations, it is preferred to perform liver biopsy with imaging guidance. This can be achieved using different methods.

Firstly, the patient can undergo this procedure under MRI or CT guidance. Unfortunately, neither of these techniques offers real-time guidance. What is more, in the case of a CT-guided procedure the patient is exposed to radiation, whereas MRI is not always feasible, especially to patients with pacemakers or metallic implants. Therefore, liver biopsy is performed mostly with ultrasound assistance [7,8]. It is a widely available, economical, and real-time imaging technique [8], but sometimes B-mode fails to deliver necessary information for safe and efficient biopsy, especially when the lesion is poorly visualised or encompasses the area of avascular tissue [9]. Some modifications have emerged to address this problem. One of them is volumetric ultrasound or so-called “3D ultrasound”. It was supposed to enhance efficiency of the biopsy by helping an operator to target the lesion. Despite initial enthusiasm few studies that were performed failed to convincingly prove its superiority over traditional B-mode [10,11].

Another potential solution that was proposed is fusion imaging. In this method images from MRI or CT are combined with those obtained from ultrasound. Through this, lesions that are barely visible on B-mode can be targeted successfully. It may sound compelling, but there are serious limitations to this method, like prolonged time of data processing and difficulties in achieving optimal overlap of images [12]. The final modification of B-mode included administration of ultrasound contrast agents (UCAs).

Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography

Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography is a diagnostic tool based on the application of the gas enclosed in microbubbles as a contrast agent. These bubbles are squeezed under the influence the acoustic wave. Subsequently, while expanding, they create a wave, which is detected by the USG transducer and shown in real-time on the screen of the device. The presentation of the scanned area changes in the course of time, as CEUS of the liver has three overlapping vascular phases because of the dual blood supply of the liver (Table 3).

Table 3

Vascular phases in contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) of the liver according to the European Federation of Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology

| Phase | Onset (sec) | End (sec) |

|---|---|---|

| Arterial | 10-20 | 30-45 |

| Portal venous | 30-45 | 120 |

| Late | > 120 | Until bubbles disappear (~240-480) |

| Post vascular | > 480 | ~half an hour |

Ultrasound contrast agents, because of their properties, vary significantly from those used in CT or MRI – they do not diffuse out of the vessels (apart from active bleeding [13]), which allows more precise assessment of wash-out (in both MRI and CT in portal and venous late phase, contrast escapes into the tumour parenchyma, which can hinder the observation of the phenomenon) [13]. What is more, with CEUS real-time imaging it is possible to visualize the early arterial phase, which is sometimes missed on MRI or CT because of less frequent image acquisition [14].

One of the important advantages of UCA is the fact that they are not excreted by kidneys and therefore can be administered safely to patients with impairment of kidney function without the risk of developing contrast-induced nephropathy or nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. Moreover, UCA, due to their biochemical character, do not disturb thyroid function and significantly less frequently provoke anaphylactoid reactions in comparison to contrast agents used in CT or MRI [9].

Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography, just like every diagnostic tool, has its limitations – most of them shared with the standard USG procedure – such as dependence of the effect on the experience and skills of the operator, and on the anatomical condition of the patient (obesity or untypical location of the lesion make it difficult to achieve optimal imaging) [13]. What is more, in most cases it is possible to assess only one FLL at the time, which leads to multiple repetition of UCA administration so as to investigate other lesions [13]. One should also always consider the risk of destruction of the microbubbles, for instance during excessive scanning in one area, which can result in a deceptive decrease of the enhancement and thus in an inappropriate diagnosis [13,15].

CEUS-guided biopsy – general principles

Practically, the essential rules of performing biopsy under CEUS guidance are similar to those of the standard US-guided procedure. Due to UCA administration, a two-step approach is necessary. Commonly, the first contrast injection is associated with target lesion characterisation and the choice of biopsy area whereas the second involves sample collection. Generally, during the second part, the clinician uses a split screen – one half for standard US view, which shows the needle more clearly, and the second for CEUS, which delivers a complex image of the liver parenchyma [16]. It is worth noting that one should perform biopsy when the lesion is best visualised, i.e. during the contrast phase, which is individual for most lesions [9].

Discussion – clinical usefulness

This review is focused on the clinical usefulness of CEUS-guided liver biopsy. The literature search was performed in 2023-2024 by means of the PubMed database. The presented cases of the patients belong to the database of Cracow’s University Hospital.

There are many crucial challenges faced during US-guided liver biopsy – namely visualisation, necrosis, and malignancy assessment.

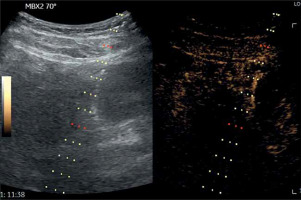

Insufficient visibility of the lesion is a problem occasionally encountered during US-guided biopsy. The question is whether contrast administration can improve the quality of imagining (Figure 2). Partovi et al. [17], in a retrospective study, showed that CEUS may be a useful technique allowing clinicians to reveal FLL when this is difficult or even impossible in traditional US examination. Typically, in such cases, CT-guided biopsy would be performed, without any earlier attempt to obtain material with US visualisation. In this study 28 patients had CEUS-guided biopsy – the results were diagnostic for 23 of them (88.5%). The drawbacks of the study such as the small study group or the absence of a control group hinder application of the results to the whole population. However, the statement of FSUMB is clear and the recommendation is as follows: CEUS-guidance should be attempted to biopsy FLLs that are invisible or inconspicuous at B-mode imaging.

Figure 2

A case of a 76-year-old woman with weakness, abdominal pain, and weight loss. Computed tomography scan revealed a lesion (red arrow), which was insufficiently visualised in classic B-mode

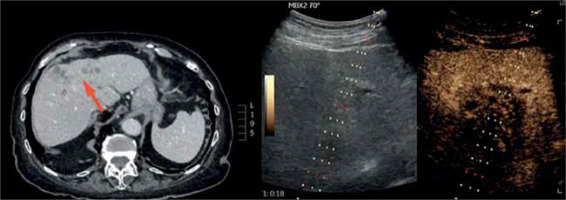

The following part concerns the problem of necrotic area sampling. CEUS may be a very useful method when the FLL contains such diifcult to detect areas in standard US (Figure 3). It was proven in a multi-centre study by Giampiero et al. [18] in which 103 patients had CEUS-guided biopsy. The examination allowed the diagnosis of 98 people with pathology confirmation.

Figure 3

A case of a 70-year-old man with anaemia of unknown origin – note the necrotic area within the lesion visible on a magnetic resonance scan (red arrow) but barely detectable in classic B-mode

Furthermore, it is said that CEUS increases the sensitivity of performed biopsies.

One of the possible explanations is that advances in the detection of necrotic areas may be associated with an increased ability to recognise necrotic tissue.

In a study published by Sparchez et al. [19] 144 patients with liver cirrhosis were referred for liver puncture due to ambiguities in CT/MRI (n = 44) or typical HCC image in CT/MRI (n = 100). The study results pointed out the statistically significant (p = 0.001) difference in sensitivity of the performed examinations: CEUS 94.74% (87.07-98.55) vs. US 74.6% (62.06-84.73). However, the results of the study should be interpreted with caution because the study design might raise objections, e.g. patients were randomised by “coin flip” method. The choice of randomisation method seems to be controversial because of the low number of participants (n = 144). For trials including less than 200 participants, other methods of randomisation are preferred [20].

To fulfil the whole image, according to EFSUMB indications, CEUS-guidance should be considered in FLLs with potential necrotic areas or if previous biopsy resulted in necrotic material.

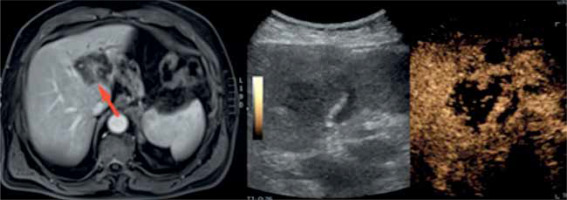

Malignancy assessment is an important aspect of CEUS examination. It is possible because of particular vascular patterns suggestive of malignancy. Moreover, CEUS allows the detection of neuroendocrine tumours or metastasis due to evaluation of wash-out phenomenon and early arterial phase, which create distinguishable motives (Figure 4). These malignancy features are collected and published by EFSUMB. To understand the LI-RADS classification created to assess the risk of malignancy of FLL, readers should delve into professional articles about this problem.

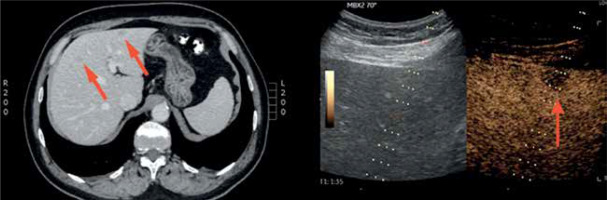

Figure 4

A case of a 63-year-old man with suspicion of liver metastases of carcinoma of unknown primary origin (red arrow on a computed tomography scan) – note wash-out phenomenon in the lesion indicated by the red arrow in contest-enhanced ultrasound scan

Furthermore, performing a biopsy is not always necessary – according to the EFSUMB approach, “If CEUS has definitively characterised a benign FLL, further investigations are not recommended to confirm the diagnosis.”

Most reports about CEUS-guided biopsy effects come from retrospective or prospective, single-centre studies with relatively modest numbers of participants. Wu et al. [21] conducted a multi-centre randomised control study, which included 2056 patients. They noticed that usage of UCA caused the change of biopsy target in as much as 25% of cases. Furthermore, they proved that CEUS – compared to US – guided biopsy is characterised by greater clinical accuracy (96% vs. 93%, p = 0.002), sensitivity (95% vs. 92%, p = 0.002), and negative predictive value (NPV – 74% vs. 57%, p = 0.001) regardless the lesion size. Such differences stood out especially for tumours smaller than 2 cm and affected the clinical accuracy (96% vs. 88%, p = 0.004), NPV (80% vs. 49%, p = 0.001), and sensitivity (95% vs. 87%, p = 0.007). What is more, in the case of tumours smaller than 2 cm, there were differences in clinical accuracy depending on the underlying cause: the parameter was significantly higher in CEUS- compared to US-guided biopsy when HCC was diagnosed (93% vs. 80%, p = 0.008), whereas in the case of metastases the clinical accuracy was comparable (98% vs. 95%, p = 0.63).

A summary of the clinical benefits gained by the choice of CEUS guidance for performing liver biopsy are available in Table 4. A successful biopsy attempt is shown in Figure 5.

Table 4

Summary of advantages of contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS)-guided liver biopsy

Conclusions

Most liver biopsies can be successfully performed under conventional USG guidance. However, in problematic cases, like poorly visible FLL or possible necrotic areas within the lesion, CEUS should be considered. It is a safe, economical, and convenient imaging technique. Its sensitivity is comparable to CT and MRI with contrast administration, but the special thing about this method is that it allows clinicians to perform and monitor biopsies in real time [18]. What is more, UCA application may increase the biopsy effectiveness, particularly due to superior FLL visualisation and necrotic/non-necrotic tissue distinction.

These features render CEUS a potent tool in contemporary diagnostics.