Introduction

Dural arteriovenous fistulas (DAVFs) represent abnormal communications between the meningeal arteries and dural venous sinuses or cortical veins. They account for approximately 10-15% of all intracranial vascular malformations, with an annual incidence of 0.15-0.29 per 100,000 individuals and with predominant involvement of the transverse-sigmoid sinus (TSS) junction. Their clinical manifestation can range from a complete absence of symptoms to emergency conditions including acute intracranial haemorrhage. The traditional classification systems of Cognard and Bordern stratify the disease risk with a primary focus on venous drainage patterns [1,2].

There have been increasing efforts to develop more holistic classification systems for DAVFs to better determine prognostic outcomes. The presence of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) as a potential pathogenetic factor for DAVFs has been postulated in the literature. It is suggested that it serves as a precursor for venous hypertension, potentially stimulates angiogenesis and causes cortical venous reflux [2-4]. Additionally, TSS occlusion (a distinct but inter-related entity to CVST) has also been repeatedly implicated in the formation of DAVFs [5].

While there are certain thrombotic factors potentially precipitating the formation of DAVFs, a certain Cognard fistula type (type II DAVFs) has also been documented to exhibit aggressive clinical behaviour. This has been attributed to the retrograde sinus flow, which leads to stasis and promotes thrombosis. The resulting venous congestion further increases reflex, thereby establishing a self-perpetuating pathogenetic loop [2,4,5].

Current classification systems do not adequately focus on the thrombosis-fistula relationships, nor do they stratify based on the risk of thrombosis, which can significantly alter therapeutic optimization. Hence, knowledge gaps persist about integration of thrombosis subtypes into the classification systems for DAVFs as well as pertaining to potential vulnerability of type II fistulas to thrombosis.

This exploratory retrospective analysis aims to determine our cumulative technical and success rates in comparison with contemporary literature. We then discuss the pathogenetic factors behind DAVFs, potential genetic predispositions and current classification systems. This leads us to address the knowledge gaps pertaining to thrombotic associations of DAVFs. We determine the relationship and/or statistical significance (if any) of thrombotic factors including CVST and TSS occlusion with embolization outcomes of DAVFs. Finally, we evaluate clinical and technical outcomes and their relationships with respect to the type of fistulas.

Material and methods

This was a single-centre retrospective analysis comprising 27 patients who presented to Aga Khan University Hospital between January 2015 and December 2023. The inclusion criteria consisted of verified diagnosis of DAVF through digital subtraction angiography (DSA) and/or cross-sectional imaging. Included patients had undergone at least one embolization session at our institute, with a minimum follow-up duration of 6 months. Patients with prior surgical interventions were excluded from the study.

The data were collected through the hospital-based health record system. The baseline characteristics included age, sex, and presenting symptoms (e.g. headache, haemorrhage).

The Cognard classification was assigned to all the cases. The clinical success of procedures was judged through complete resolution of symptoms on the first or subsequent follow-up visits. Technical success was defined as either complete or partial embolization of the DAVFs during the interventional procedures. Complete technical success was defined as 100% obliteration of the fistula on angiographic images, and partial technical success included cases with 80% or more embolization but not falling within the complete subtype.

Further procedural details recorded included the site of fistulas, whether there was associated CVST, potential occlusion of the TSS, and any potential recanalization events. Data on any potential complications during the procedures and recurrence events on follow-up visits were also collected.

Statistical analysis

The mean and standard deviation were calculated for age. The categorical variables were assessed through calculation of frequency and percentages. For the most common fistula types in the dataset, Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed) was used to assess for any significant correlation between fistula types, clinical and technical success, as well as recurrence and complications. The same statistical test was employed to test associations of the presence of TSS occlusion and CVST with other variables. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analysed through IBM Statistics SPSS version 26.

Results

A total of 27 patients underwent embolization procedures for DAVFs between 2015 and 2023 at our institute. The mean age was 44.07 years with a standard deviation of 16.45 years (range: 8-73 years) with the male patients forming the majority of the cohort (23/27, 85%). The most common presenting symptom was headache, noted in 11 out of 27 patients (41%) (Table 1). With regards to the classification of fistulas, the predominant category was Cognard type IV, comprising 13 out 27 cases (48%). The second most common classification was type II fistulas, which were observed in 11 out of 27 patients (44%). Two patients also presented with type 1 fistulas (Table 1).

Table 1

Summary table of patient characteristics and fistula types

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 42.59 ± 19.42 |

| Most common symptom, n (%) | |

| Headache | 11 (40.7) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 23 (85.2) |

| Female | 4 (14.8) |

| Fistula type, n (%) | |

| Type I | 2 (7.4) |

| Type II | 11 (44.4) |

| Type IV | 13 (44.4) |

| Type V | 1 (3.7) |

| Clinical success#, n (%) | |

| Complete | 11 (44) |

| Partial | 14 (56) |

| Technical success, n (%) | |

| Complete | 17 (63) |

| Partial | 10 (37) |

| Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis#, n (%) | |

| Yes | 11 (41) |

| No | 16 (59) |

| Associated transverse-sigmoid sinus occlusion, n (%) | |

| Yes | 13 (48) |

| No | 14 (52) |

| Recanalization, n (%) | |

| Yes | 5 (18.5) |

| No | 22 (81.5) |

| Complications, n (%) | |

| Yes | 5 (18.5) |

| No | 22 (81.5) |

| Recurrence, n (%) | |

| Yes | 4 (19) |

| No | 21* |

Complete technical success was achieved in 17 out of 27 patients (63%), whereas partial angiographic embolization of the fistula was achieved in 7 out of the 10 remaining patients. Two of the patients were lost to follow-up. In the remaining 25 patients, complete clinical success was achieved in 11 patients (44%), who reported complete resolution of symptoms. In 12 of the remaining 14 patients, there was significant clinical improvement in symptoms. One of the patients developed a large subdural haematoma during the procedure and had to undergo surgery. One other patient reported resolution of headaches but no significant improvement in vision (Table 2).

Table 2

Clinical and technical success according to fistula types

| Fistula type | Complete | Partial | Total | % Complete |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical success (complete vs. partial) | ||||

| Type I | 1 | 1 | 2 | 50.0 |

| Type II | 5 | 6 | 11 | 45.5 |

| Type IV | 10 | 3 | 13 | 76.9 |

| Type V | 1 | 0 | 1 | 100.0 |

| Overall | 17 | 10 | 27 | 63.0 |

| Clinical success (complete vs. partial) | ||||

| Type I | 1 | 1 | 2 | 50.0 |

| Type II* | 2 | 8 | 11 | 20 (out of 10 patients) |

| Type IV* | 8 | 4 | 13 | 67 (out of 12 patients) |

| Type V | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.0 |

| Overall | 11 | 14 | 27 | 44 (out of 25 patients) |

Recanalization was observed in 5 out of 27 procedures. This was treated with angioplasty in 3 of the cases, whereas stenting was employed in the remaining 2 cases (Table 1).

Complications were observed in 5 out of 27 (18.5%) cases. These included hemiparesis, mild facial weakness, and subdural and subarachnoid haemorrhages. In one of the cases, a tiny fragment of a microcatheter was broken off, which led to small emboli in the distal branches of the middle cerebral artery. However, it did not result in any post-procedural focal neurological deficit.

In 6 out of 27 patients, recurrence information could not be assessed due to inability to establish communication with the patients. In the remaining 21 patients, 4 reported varying degrees of recurrence, among whom one presented with sinus re-occlusion. An attempt of fistula embolization was made via a venous route in one patient, while another patient with recurrence was treated with stenting of the right transverse sinus.

Among 27 patients, 9 (33.3%) exhibited both TSS occlusion and CVST (Table 3). This subgroup showed universally poor outcomes (0% clinical success, 44.4% complications) (Table 8). Despite this overlap, TSS occlusion and CVST independently predicted significant associations with type II fistulas and reduced clinical success when analysed separately (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 3

Outcomes for thrombosis subtype groups (including overlap)

| Group | Patients (n) | Clinical success | Technical success | Complications | Recurrence* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSS only | 4 | 1/4 (25.0%) | 3/4 (75.0%) | 1/4 (25.0%) | 0/3 (0.0%) |

| CVST only | 2 | 0/2 (0.0%) | 1/2 (50.0%) | 1/2 (50.0%) | 0/1 (0.0%) |

| Both (TSS+CVST) | 9 | 1/9 (11.1%) | 5/9 (55.6%) | 4/9 (44.4%) | 3/7 (42.9%) |

| Neither | 12 | 9/12 (75.0%) | 8/12 (66.7%) | 0/12 (0.0%) | 1/10 (10.0%) |

| Statistical test | – | *p = 0.0007† | *p = 0.42† | *p = 0.003† | *p = 0.12† |

Table 4

Transverse-sigmoid sinus (TSS) occlusion and associations

| Association | TSS occlusion present (n = 13) | TSS occlusion absent (n = 14) | p-value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type II fistulas | 9/13 (69.2%) | 2/14 (14.3%) | 0.003 | Significant |

| Type IV fistulas | 4/13 (30.8%) | 9/14 (64.3%) | 0.123 | Not significant |

| Technical success | 8/13 (61.5%) | 9/14 (64.3%) | 1.000 | Not significant |

| Clinical success* | 3/12 (25.0%) | 8/13 (61.5%) | 0.035 | Significant |

| Complications | 4/13 (30.8%) | 1/14 (7.1%) | 0.168 | Not significant |

| Recurrence** | 3/10 (30.0%) | 1/11 (9.1%) | 0.329 | Not significant |

Table 5

Presence of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) and associations

| Association | CVST present (n = 11) | CVST absent (n = 16) | p-value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type II fistulas | 7/11 (63.6%) | 4/16 (25.0%) | 0.044 | Significant |

| Type IV fistulas | 4/11 (36.4%) | 9/16 (56.3%) | 0.451 | Not significant |

| Technical success | 6/11 (54.5%) | 11/16 (68.8%) | 0.704 | Not significant |

| Clinical success* | 0/9 (0.0%) | 9/15 (60.0%) | 0.0009 | Significant |

| Complications | 4/11 (36.4%) | 2/16 (12.5%) | 0.172 | Not significant |

| Recurrence** | 2/8 (25.0%) | 2/13 (15.4%) | 0.621 | Not significant |

Table 6

Outcomes in type II vs. non-type II fistulas

Table 7

Comparison between outcomes of type II vs. type IV fistulas

Table 8

Outcome correlation of type IV vs non-type IV fistulas

Out of the 27 patients, the venous drainage at the junction of the TSS was occluded in 13 patients, contributing to 48% of the patient cohort. TSS occlusion showed a significant association with type II fistulas (p = 0.003). It also showed a significant correlation with lower clinical success rates (25.0% vs. 61.5%, p = 0.035) (Table 4).

There was associated CVST in 11 out of 27 patients (41%). The presence of CVST strongly correlated with type II fistulas in our dataset (63.6% vs. 25.0%, p = 0.044). Complete clinical success was also absent in all the patients who presented with CVST (0% complete success vs. 60%, p = 0.0009). In patients with CVST, there were also higher rates of complications (36.4% vs. 12.5%), but this was not statistically significant (Table 5).

With regards to outcomes according to fistula types, complete clinical success rates in the two most common fistula groups in our dataset, type II and type IV, were 18% and 62%, respectively. The complete technical success rates in type II and type IV fistulas were 46% and 77%, respectively (Table 2). We also aimed to assess any significant correlation between the types of fistulas and their clinical and technical outcomes as well as their complication rates and recurrence. Since the two most common types were type IV (13 out of 27) and type II fistulas (11 out of 27), the data were divided into binary groups with one group containing the aforementioned fistula types and the other group containing the rest of the data items.

In relation to type II fistulas, we did not observe any significant correlation between the fistula type and clinical success (p = 0.07), technical success (p = 0.27), complications (p = 0.65) or recurrence (p = 1.00) (Tables 6 and 7).

In relation to type IV fistulas, however, we observed a significant correlation between clinical success and type IV fistulas versus the non-type IV group (p = 0.04). Other factors such as technical success (p = 0.13), recurrence (p = 1.00) and complication (p = 1.00) rates did not show any significant correlation between the type IV versus non-type IV groups (Tables 7 and 8).

Discussion

DAVFs are abnormal connections between the dural arteries and dural venous sinuses, meningeal veins or the cortical veins [6]. The key distinction between DAVFs and pial arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) lies in the location of the arteriovenous shunt and the presence or absence of a parenchymal nidus. In DAVFs, the arteriovenous communication occurs within the dura mater, involving dural arteries, and there is no parenchymal nidus, in contrast to pial AVMs [6-8]. DAVFs have been largely documented as idiopathic; however, there is evidence in the literature of preceding events involving dural sinus thrombosis, trauma, infection and/or prior craniotomy [9]. The presence of associated CVST and resultant venous hypertension is a common occurrence with DAVFs [10]. In our retrospective cohort of 27 patients, we achieved complete technical and clinical success rates of 63% and 40.7%, respectively. In the literature, single-centre studies with limited sample sizes have documented a technical success rate of 75-94% [11,12]. The slight difference can be attributed to our definition of complete technical success being total fistula obliteration on angiography, whereas cases with 80% and above obliteration rates were documented as partial technical success. Similarly, we achieved a complete cure of symptoms in 40.7% of the patients, while the rest showed marked improvement in symptoms on followup visits. Cumulatively, we achieved complete or near-complete symptom resolution in the entire cohort. This is comparable with literature in which a recent metaanalysis showed that embolization of anterior cranial fossa DAVFs was associated with symptom resolution of 94-98% [13].

In our cohort, the complication rates and recurrence rates were 18.5% (5 out of 27) and 19% (4 out of possible 21), respectively. This is comparable to a retrospective cohort study evaluating embolization outcomes of high grade DAVFs, in which the complication and recurrence rates were 20% and 13.1%, respectively [14]. The most common complications after DAVF embolization are neurological deficits and ischaemic events [13].Our study reported similar complications including hemiparesis, mild facial weakness, and subdural and subarachnoid haemorrhages.

The exact pathogenetic mechanism behind DAVFs has been debated in the literature; however, thrombosis and venous hypertension have been repeatedly identified as two primary triggers for the pathology. The occurrence of prior asymptomatic thrombosis of the dural venous sinuses, possible association with inherited prothrombotic states such as protein C or S deficiency, and/or trauma are all thought of as trigger events for DAVFs. The presence of venous flow obstruction with resultant elevation of local pressure results in the creation of abnormal arteriovenous shunts [1,12,15]. DAVFs often lead to cognitive impairment, which can be due either to thalamic involvement in cases of associated deep venous drainage, or to cortical venous hypertension as a result of disruption in the superficial venous drainage system of the cortex and the subcortical white matter, or a combination of both of these aetiologies [16]. Chronic venous congestion can upregulate hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1a) and vascular endothelial growth factor. This drives angiogenesis, with resultant capillary proliferation and arterialization of small calibre vessels within the dura mater [15].

The association of underlying genetic mutations with intracranial DAVFs has been sporadically studied in the literature. A case report described the presence of a mutation in the low-density lipoprotein receptor gene (LDLR) in a patient with CVST and co-existing DAVFs. These mutations can disrupt lipid metabolism, leading to a hypercoagulable state and venous thrombosis. The chronicity of the latter can cause venous hypertension and angiogenesis, which may result in the development of a DAVF [17]. A prothrombin G20210A mutation has also been identified as potentially predisposing to venous sinus thrombosis with resultant venous hypertension and angiogenic remodelling. A case report identified two sisters with intracranial dural AVMs with the aforementioned mutation [18]. A cohort study consisting of 116 patients also identified that thrombophilic polymorphisms including prothrombin mutations have a higher frequency in patients with DAVFs as compared to the general population [19]. Similarly, another retrospective cohort study evaluating the presence of hereditary thrombophilia in patients with DAVFs revealed that the prevalence of a factor V Leiden mutation was 18% in the patient cohort versus 5% in the general Caucasian population [20]. While genetic mutations, particularly thrombophilias, are implicated in the pathogenesis of DAVFs, they are not the sole causative factors. The role of screening for pro-coagulable states and thrombophilia mutations in patients with DAVFs remains debated in the literature.

The classification of DAVFs has evolved significantly from the initial systems focusing on venous drainage pathways to current attempts aiming to inculcate anatomical and haemodynamic stratifications. The Borden and Cognard classifications, established in 1995, provide a foundational structure for classification of DAVFs. Under the Borden system, DAVFs were categorized into three types based on the site of venous drainage and the presence of cortical venous reflux. This was expanded into five categories under the Cognard classification which incorporated the direction of sinus flow (antegrade vs. retrograde) as well as venous ectasia (Figures 1-3 show multiple types of dural arteriovenous fistulas) [1,2]. The presence of cortical venous drainage in both classification schemes serves to stratify lesions according to aggressiveness. Borden type I, Cognard I and II do not have cortical venous drainage and usually have benign clinical histories. Borden types II/III and Cognard IIb-V present with cortical venous drainage are more aggressive, with haemorrhagic risk as high as 65% noted within type IV Cognard fistulas [1,21].

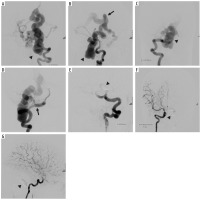

Figure 1

Digital subtraction angiography showing dural arteriovenous fistula in posterior cranial fossa, between ectatic meningeal artery – direct branch of left vertebral artery – and ectatic cortical vein (fistula indicated by arrowheads in A, B and C and ectatic meningeal branches indicated by full black arrow in D). The ectatic cortical vein had venous return through ectatic vein of Gallen, central vein, bilateral cavernous and right internal jugular vein (venous return indicated by full black arrow in B). Detachable balloons were placed at the site of arteriovenous fistula, and then 3 further detachable coils were placed proximally to the balloon. Post-procedural three-vessel angiogram showing complete exclusion of the dural arteriovenous fistula (indicated by arrowheads in E, F and G)

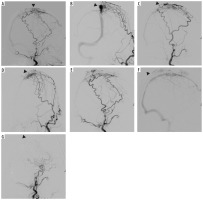

Figure 2

Digital subtraction angiography showing anterior dural arteriovenous fistula, between anterior segment of superior sagittal sinus and branches of bilateral temporal arteries, a few feeders of bilateral occipital arteries and ethmoidal branches of bilateral ophthalmic arteries (indicated by black arrowheads in images A-D). A branch of the left superficial temporal artery was cannulated distally with a microcatheter. Embolization was performed using ONYX (6cc). This caused maximum fistula closure. Subsequently, microcatheter cannulation of right temporal artery was also performed and embolization was performed using PVA 355-500. Post-embolization angiogram shows almost 90-95% embolization of the fistula occlusion (indicated by black arrowheads in images E-G)

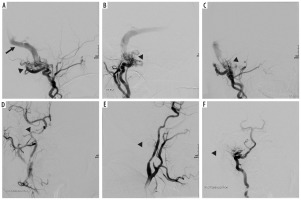

Figure 3

Digital subtraction angiography showing complex dural arteriovenous fistula, which was supplied by numerous feeders from right occipital, right sided ascending pharyngeal, posterior auricular and right vertebral artery. Venous return through occluded pouch of right sigmoid sinus, which then further flowed retrogradely into transverse and superior sagittal sinus and from there into superficial cortical veins and then into deep venous system, with final drainage into cavernous sinus, inferior petrosal sinus and ophthalmic vein (black arrowheads showing the fistula in images A-C, black arrow indicating venous return in image A). Subsequently, a microcatheter was placed in the right occipital artery and its embolization was performed using Onyx. Furthermore, using a separate microcatheter, cannulation of right ascending pharyngeal and posterior auricular arteries was performed one by one, followed by their embolization using Onyx procedure; angiogram shows 90% embolization of the feeders achieved. Minor filling was noted from vertebral feeder. Sluggish flow of the contrast from vertebral artery feeders was noted. Venous phase showed contrast stasis in transverse and superior sagittal sinuses (post-embolization sites indicated by arrowheads in images D-F)

The need to update the traditional classification systems discussed above arises from factors such as communication with the venous sinus, determining risk based on symptomatic presentation, and, importantly, thrombotic associations can significantly alter prognostic outcomes.

A key update is the sinus versus non-sinus classification, which addresses limitations in traditional systems by emphasizing the fistula’s anatomical relationship to dural sinuses. Sinus-type DAVFs involve direct shunting between dural arteries and a venous sinus, sometimes secondarily recruiting cortical veins (“red veins”), whereas non-sinus types arise within the dural leaflets themselves, draining exclusively into cortical veins without sinus communication [6,22,23]. The differentiation can prove to be crucial, as the sinus type fistulas require obliteration and occlusion of the involved veins, whereas the non-sinus types of fistulas warrant aimed disconnection at the proximal draining vein or the red vein [22,23]. The non-sinus fistulas located in the tentorium cerebelli and the anterior cranial fossa tend to exhibit aggressive neurological symptoms, with anterior fossa DAVFs exhibiting ranges of intracerebral haemorrhage of 44 to 84% [6,24].

Zipfel’s classification proposed in 2009 stratifies aggressive DAVFs based on the severity of symptoms and natural clinical history [23]. This was also evaluated by a retrospective study focusing on 143 patients with DAVFs. The study revealed worse clinical symptoms in type II and type III fistulas according to the classification, necessitating aggressive endovascular treatment [25]. Additionally, a proportion of DAVFs exhibit a dynamic nature whereby low-grade lesions may evolve to high-grade via venous thrombosis or flow-related angiogenesis. This warrants serious monitoring even for initially non-aggressive cases [2,6].

However, updates regarding angiogenesis secondary to thrombosis are limited and current systems fail to address the fact that CVST can trigger vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) driven fistula formation through hypoxic signalling [26].

Multiple studies have reported that DAVFs can develop after CVST [3,27-29]. A study revealed that 13.3% of all patients presenting with cerebral venous thrombosis also had DAVFs [27]. Similarly, a study conducted on 1218 adult patients from the international CVST consortium found that the prevalence of DAVFs was 2.4%, which is higher than that of the general population [3].

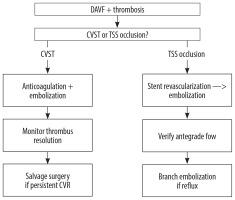

According to our knowledge, there are no definitive controlled studies that compare clinical outcomes between DAVFs patients with CVST and those without it. Within the confines of an exploratory analysis, our study revealed that 11 out of 27 patients (41%) presenting with DAVFs also had CVST, which was associated with significantly poorer clinical outcomes (p = 0.0009) (Table 7) as compared to the non-CVST subset. This could be attributable to the fact that we accounted for clinical success in binary groups (complete vs. non-complete), and the CVST subset could have been associated with partial clinical success. Nevertheless, the presence of CVST can obscure or delay the diagnosis of DAVFs, which could increase the risk of haemorrhage. Patients presenting with both CVST and DAVFs may require a combination of treatments including anticoagulation, endovascular therapy (embolization or stenting) and sometimes surgery. The choice requires a tailored and individualized approach taking into consideration complications such as intracranial haemorrhage [30-32].

TSS junction occlusion is a specific type of venous outflow obstruction which results in localised venous hypertension and promotes the formation of DAVFs at or near the TSS junction. TSS occlusion is associated with more complex DAVFs and potentially worse outcomes. A retrospective study found that DAVFs following CVST were most frequently located at the TSS (46.7%), and these cases often required endovascular intervention [29]. In our study, TSS occlusion was present in 13 out of 27 patients (48%), and this was significantly associated with lower rates of clinical success (p = 0.035) (Table 6).

These mechanistic differences between general CVST and specific TSS occlusion necessitate tailored interventions: CVST requires combined anticoagulation and embolization to dissolve thrombotic nidi and occlude fistulous tracts, while TSS occlusion requires stent revascularization preceding embolization to normalize pressure gradients [28-30]. Integrating these subtypes (CVST vs. TSS occlusion) into DAVF classifications (e.g., Borden/Cognard suffixes) could help guide aetiology-specific therapy.

While our analysis treated TSS occlusion and CVST as independent variables, 33.3% of patients exhibited both conditions. Future studies should analyse this high-risk subgroup separately using pathophysiology-driven protocols. The presence of this dual pathology can potentially reduce the efficacy of embolic therapy owing to micro-thrombosis and endothelial hyperplasia [33].

This critical difference in management pathway is summarized below in Figure 4.

Our study also provided interesting insights with regards to outcomes associated with type II Cognard fistulas. They exhibited disproportionately poor outcomes, possibly due to their synergy with thrombosis. In our data, they were associated with TSS occlusion in 69.2% (*p* = 0.003) and with CVST in 63.6% (*p* = 0.044), driving cortical venous reflux that reduces clinical success to 20% versus 67% in type IV. This aligns with haemodynamic studies showing that thrombosis amplifies venous hypertension in type II, accelerating cortical venous reflux progression [29]. Type IV fistulas maintained 76.9% technical and 67% clinical success despite high-grade status, which may be attributable to two factors: 1) Only 23.1% exhibit CVST/TSS comorbidity versus > 60% in type II, minimizing thrombotic angiogenesis; and 2) non-sinus drainage patterns enable targeted embolization of the proximal draining vein without requiring flow correction [28,29]. Consequently, type IV outcomes remain favourable unless complicated by thrombosis (success drops to 23.1% when CVST coexists), while type II’s inherent thrombosis susceptibility necessitates combined haemodynamic and thrombotic management even in “cured” cases. This underscores the imperative for classification systems to codify thrombosis subtypes, as their intersection with fistula architecture dictates therapeutic efficacy more profoundly than traditional grading alone.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. This is a retrospective, single-centre study, which may have resulted in inherent selection bias. Additionally, the small sample size might have reduced the statistical power of the study, particularly for subgroup analyses (dual TSS occlusion + CVST), increasing the risk of type II errors. Some of the patients were lost to follow-up for recurrence and clinical success data, which may underestimate true event rates. We chose to dichotomize clinical success (complete vs. non-complete), which may ignore subtle but meaningful improvements, especially in CVST-associated cases where partial recovery is plausible. There were also some unmeasured confounders such as absence of data on anticoagulation duration, thrombophilia screening, or genetic mutations (e.g., factor V Leiden, Prothrombin G20210A), which might have introduced unwarranted heterogeneity in thrombotic risk.

Conclusions

This exploratory retrospective analysis highlights critical insights into the influence of thrombotic phenotypes (CVST and TSS occlusion) on DAVF embolization outcomes, independent of traditional Cognard grading. Type II fistulas, in particular, emerge as a subset with high vulnerability, exhibiting thrombotic comorbidity and disproportionately poor clinical success. These findings support the integration of thrombosis subtypes into DAVF classifications (e.g., Cognard-CVST/TSS suffixes) to stratify risk and guide aetiology-specific therapy – anticoagulation ± stenting for TSS occlusion versus isolated embolization for non-thrombotic lesions. However, multicentre and large-scale studies are needed to evaluate these associations. Establishing a prospective, multicentre registry with standardized thrombophilia screening and long-term neuroimaging may be essential to validate this paradigm shift, refine therapeutic algorithms, and improve outcomes in thrombosis-associated DAVFs.