Introduction

Pulmonary regurgitation (PR) is a common problem in patients with repaired tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) [1-6]. PR has been shown to have a detrimental impact on right ventricular (RV) size and function in various patient populations [5,7-14]. Additionally, ventricular performance and size can be compromised by other pathologies such as valvular insufficiency at a valve other than the pulmonary valve (e.g. tricuspid regurgitation) and/or residual ventricular septal defect (VSD) [1-3].

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) is considered the diagnostic modality of choice for evaluating the right ventricle [1-4,15]. Unlike echocardiography, it enables the complex RV anatomy and function to be assessed accurately and reproducibly [1-5,15,16].

Concomitant haemodynamic abnormalities (significant tricuspid regurgitation, residual ventricular septal defect – VSD) are often observed in patients after repair of TOF [1-4,17-19]. To date, there have been no studies addressing the influence of PR on the right ventricle in patients with repaired TOF and additional haemodynamic abnormalities. It has been demonstrated that right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) obstruction (RVOTO) is a confounding (protective) factor in assessing how PR impacts RV size and function in patients with repaired TOF [20]. We hypothesised that a potential protective effect of RVOTO on RV size and performance is hampered in patients with additional haemodynamic abnormalities. Additionally, we aimed to assess the impact of PR on RV size and function in patients with repaired TOF and concomitant haemodynamic abnormalities. To evaluate these issues, we decided to perform the current study.

Material and methods

The study population included consecutive patients with repaired TOF repair, who had undergone a CMR study. Patients with more than mild tricuspid regurgitation (as assessed by echocardiography) and/or residual VSD were included. Exclusion criteria comprised the following: (1) poor quality of CMR images, (2) incomplete CMR study, (3) incomplete echocardiographic dataset, (4) no echocardiographic assessment performed within one year of CMR study, (5) extracardiac shunt, (6) more than mild regurgitation at a valve other than pulmonic or tricuspid valve, and (7) absence of additional haemodynamic abnormalities.

All patients underwent transthoracic echocardiography with commercially available systems. Peak instantaneous RVOT gradient was calculated with the use of the Bernoulli equation on the basis of the maximal velocity across RVOT. Peak gradient greater or equal to 30 mm Hg was considered significant [1]. All patients were screened for the presence of residual VSD and/or significant (at least moderate) regurgitation at a valve other than the pulmonary valve.

All CMR imaging studies were performed with a 1.5 T system (Avanto, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). The volumetric analysis of the right and left ventricles was performed on the basis of short axis balanced steady-state free precession breath-hold images with the use of dedicated software (Mass 6.2.1, Medis, Leiden, Netherlands). Epicardial and endocardial borders were outlined manually at end-systole and end-diastole. On the basis of these data, the following parameters were calculated: RV end-diastolic volume (RVEDV), RV end-systolic volume (RVESV), RV stroke volume (RVSV), RV ejection fraction (RVEF) and RV mass (RVM), left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic volume (LVEDV), LV end-systolic volume (LVESV), LV stroke volume (LVSV), LV ejection fraction (LVEF), and LV mass (LVM). All parameters were indexed for body surface area (BSA). The trabeculae and papillary muscles were included in blood pool. Imaging parameters were as follows: effective repetition time 33 to 54 ms, echo time 1.2 ms, flip angle 64° to 79°, slice thickness 8 mm, gap 1.6 mm, in plane image resolution 1.6 × 1.6 mm to 1.8 × 1.8 mm, and temporal resolution 25 to 40 phases per cardiac cycle. A flow sensitive gradient echo sequence acquired during free breathing (effective repetition time 30 to 47 ms, echo time 2 ms, flip angle 30°, slice thickness 5 mm) and dedicated software (Argus, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) were used for the calculation of pulmonary forward and backward flows. The imaging plane was located at the midpoint of the main pulmonary artery or conduit and prescribed perpendicular to the vessel by the double oblique technique, PR fraction (PRF) was calculated as percentage of backward flow over forward flow, and PR volume (PRV) as a total reverse flow indexed for BSA. PRF ≥ 20% was considered significant PR [13,14]. All CMR studies were screened for the presence of extracardiac shunt (e.g. major aortopulmonary collateral arteries).

All variables were tested for normal distribution with the use of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Normally distributed variables were expressed as mean ± SD. Correlations were expressed with the Pearson rank correlation coefficients. Comparisons between continuous variables with normal distribution were performed with the use of the t-test for unpaired samples. A probability value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted with the use of Medcalc statistical software, version 10.0.2.0 (MedCalc, Mariakerke, Belgium).

The local Research Committee approved of the retrospective review of medical records and computer databases. Each patient gave their informed consent for participation in the CMR study.

Results

Out of 90 patients with repaired TOF, who had undergone CMR, 18 individuals met the inclusion criteria. Patients with poor quality of CMR images precluding analysis (n = 3), incomplete CMR study (n = 1), incomplete echocardiographic dataset (n = 2), no echocardiographic assessment performed within one year of CMR study (n = 3), extracardiac shunt (n = 1), more than mild regurgitation at a valve other than the pulmonic or tricuspid valve (n = 1), and those with no additional haemodynamic abnormalities (n = 61) were excluded from the analysis. The remaining patients (n = 18) formed the study population.

Twelve patients (66.7%) underwent CMR and echo studies on the same day. In four patients (22.2%), an echo study was performed within 30 days of a CMR study. The clinical characteristics of the study population are summarised in Table 1. Table 2 presents the CMR and echocardiographic characteristics.

Table 1

Baseline characteristics of the study population

Table 2

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance and echocardiographic characteristics of the study population

[ii] LVEDV – left ventricular end-diastolic volume, LVEF – left ventricular ejection fraction, LVESV – left ventricular end-systolic volume, LVM – left ventricular mass, LVSV – left ventricular stroke volume, RVEDV – right ventricular end-diastolic volume, RVEF – right ventricular ejection fraction, RVESV – right ventricular end-systolic volume, RVM – right ventricular mass, RVSV – right ventricular stroke volume, PRF – pulmonary regurgitation fraction, PRV – pulmonary regurgitation volume, RVOT – right ventricular outflow tract

In nine patients (50%) the peak gradient across RVOT was ≥ 30 mm Hg. There were no differences between patients with and without RVOTO in RV size and function either in the whole group (RVEDV: 158.8 ± 62.5 ml/m2 vs. 160.8 ± 35.2 ml/m2; p = 0.92, RVESV: 87.7 ± 56.5 ml/m2 vs. 84.1 ± 29.0 ml/m2; p = 0.87 and RVEF: 47.8 ± 11.4% vs. 48.4 ± 11.5%; p = 0.9) or in patients with significant PR (RVEDV [p = 0.94]; RVESV [p = 0.65]; RVEF [p = 0.36]).

Neither PRF nor PRV correlated with RVEDV or RVESV (Table 3). Similarly, no significant correlations were observed between PRF or PRV and RVEF (Table 3). In a subgroup of patients with significant PR (n = 13), the relationship between the degree of PR (measured as PRF or PRV) and RV size and function was even poorer (Table 3).

There were no correlations between peak RVOT gradient and RVEDV, RVESV, or RVEF (Table 3).

Table 3

Correlations between pulmonary regurgitation fraction, pulmonary regurgitation volume, peak right ventricular outflow tract gradient vs. right ventricular volumes and right ventricular ejection fraction

[i] RVEDV – right ventricular end-diastolic volume, RVEF – right ventricular ejection fraction, RVESV – right ventricular end-systolic volume, RVM – right ventricular mass, RVSV – right ventricular stroke volume, PRF – pulmonary regurgitation fraction, PRV – pulmonary regurgitation volume, RVOT – right ventricular outflow tract

Discussion

It has been previously presented that RVOTO acts as a protective factor in the assessment of PR impact on RV size and function in patients after TOF repair [20]. However, in our study comprising a population with additional haemodynamic abnormalities, we found no differences in RV size and function between patients with and without RVOTO. Previous studies in various patient populations after TOF repair demonstrated a linear relationship between PR and RV volumes [11-13,21]. These studies included both unselected patient populations as well as patients without tricuspid regurgitation and/or residual VSD. In a selected patient population with additional haemodynamic abnormalities, we have proven that neither measures of PR nor peak RVOT gradient correlated with RV size and RVEF. Therefore, other haemodynamic pathologies such as tricuspid regurgitation or residual VSD have to be considered when the impact of PR on RV is assessed.

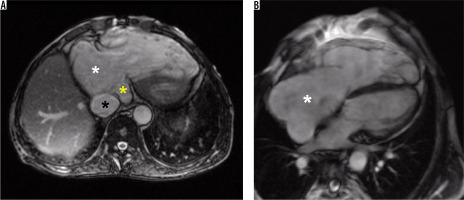

Figure 1

Representative cardiac magnetic resonance images in a patient with significant tricuspid regurgitation and its consequences. A) Steady-state free precession single shot axial image demonstrating severely dilated right atrium (white asterisk), dilated vena cava inferior (black asterisk), and dilated coronary sinus (yellow asterisk). B) Steady-state free precession 4-chamber view cine image demonstrating severely dilated right atrium

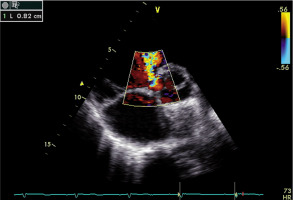

Figure 2

Representative echocardiography image in a patient with residual ventricular septal defect (VSD). Parasternal colour Doppler short-axis view demonstrating VSD of a diameter of 8 mm

The causes of lack of relationship between PR and RV size and function are multifactorial. First, in 33.3% of patients more than mild regurgitation at a valve other than the pulmonary valve, mainly ≥ moderate tricuspid regurgitation (n = 6) was observed, which causes extra volume burden on the RV and leads to RV dilatation. Secondly, although isolated VSD does not cause RV enlargement, guidelines on congenital heart disease indicate that in patients with repaired TOF a combination of residual VSD, RVOTO, and/or PR leads to progressive RV dilatation and impaired RV systolic function [1,3]. Finally, the mean RVEDV in the study group was close to 170 ml/m2, which is considered as severe RV dilatation [21,22]. It can be speculated that in patients with severe RV enlargement the volume overload of PR may not cause a relationship between PR and RVEDV or RVESV.

The findings of our study may be clinically relevant when a decision is made about performing pulmonary valve replacement. One could expect that the bigger PR is, the larger RV size (volume) is observed. However, as presented in our study, this notion did not hold true for the population studied, because no correlation between PR severity and RVEDV was noted. Consequently, the decision about performing pulmonary valve replacement may be influenced by this false opinion.

We have no data concerning the onset of additional haemodynamic abnormalities relative to the TOF repair or relative to the CMR examination. It is, therefore, unknown whether those pathologies were present in all patients since the time of the TOF repair. This needs to be elucidated in further studies.

We used two different software solutions (Mass by Medis and Argus by Siemens), as available in our centre, for quantitative analyses, which can be considered as a limitation. However, this approach is rather common in CMR studies because different software is used for ventricular size and function analysis than for flow estimation.

Although CMR estimates of RVOT gradient pressure show better (versus echocardiography) correlation with the findings of cardiac catheterisation, according to guidelines for the management of congenital heart diseases we decided to use echocardiography to calculate the peak RVOT gradient [1-4,24].

This is a preliminary report, and the number of patients is relatively small and might seem not large enough to make reasonable conclusions. However, CMR is characterised as the most reproducible non-invasive method of assessing ventricular size and function. This in turn enabled us to limit the number of patients needed to detect a statistically significant difference [25,26]. Nevertheless, because of the small patient number and the heterogeneity of concomitant lesions, the results of the current study should be confirmed or refuted through larger trials.

Computed tomography is ideally suited to the detection of various other congenital abnormalities of the cardiovascular system in patients with TOF [27]. Therefore, it should be elucidated whether incorporation of this technique provides additional information to interpret the findings of our study. Further studies aimed at ascertaining how to incorporate these abnormalities into clinical decision making are needed.

Conclusions

The potential protective effect of RVOTO on RV size and performance may be hampered by other haemodynamic abnormalities. There are no significant relations between measures of PR and RV volumes in patients after TOF repair with concomitant haemodynamic abnormalities. These abnormalities act as confounding factors in assessing how PR impacts RV size and function.