Introduction

Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) results from a perinatal hypoxic, ischemic, and/or asphyxial event and is the most common cause of neonatal encephalopathy [1]. The population incidence of perinatal HIE is 1.7 per 1000 births [2]. A recent meta-analysis showed that therapeutic hypothermia (TH), applied to children with HIE, can reduce neurological disabilities and the incidence of cerebral palsy in various clinical settings. However, its effects on neonatal, infantile and childhood mortality remain unclear. It does not appear to influence the occurrence of neonatal seizures or the development of epilepsy during infancy and childhood. On the other hand, neonates treated with TH showed more favorable outcomes in terms of electroencephalogram abnormalities and various magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings [3]. Importantly, TH remains the only proven treatment for neonatal HIE [4].

MRI is a key diagnostic, non-invasive tool used to visually assess acquired brain changes associated with HIE and the progression of brain injury. Even in the absence of MRI abnormalities, newborns with significant HIE are at high risk for neurodevelopmental complications. These complications may include poor performance in developmental assessments, delayed language skills, and issues related to emotional processing, sensory movement, learning and memory [5]. It is essential to recognize these risks. Since certain brain injuries may not be readily apparent on standard MRI scans, the increasing use of advanced volumetric imaging techniques allows for a more precise and comprehensive assessment of brain structure. Volumetric software, such as FreeSurfer [6], FMRIB Software Library (FSL) [7], and Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) [8], provide detailed measurements of brain volume and structural changes in brain structures. Alterations in structural volumes could help in identifying early signs of neurodevelopmental impairments.

The aim of this review is to analyze and summarize the volumetric differences observed in the brains of children with HIE after TH, focusing on volumetric MRI findings and their implications for long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Structural volume differences

In the following sections, we discuss the volumetric changes observed in several structures in the brain, including the thalamus, cerebellum, basal ganglia and hippocampus. The summary of studies and key findings are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Summary of key findings and volumetric differences in brain structures in hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) studies

| Authors, year and reference | Age at scanning | Participant characterristics | MRI/volumetric software | Key results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kebaya LMN et al., 2023 [9] | 4 days | SG: 28 (23 – TH) CG: 28 | SG: 1.5T GE CG: 3T Philips Achieva Freesurfer | ↓ Hippocampus R ↓ Basal ganglia R and L ↓ Thalamus R and L ↓ Cerebellum R ↔ Amygdala, hippocampus L, cerebellum L |

| Spencer APC et al., 2023 [10] | 6-8 years | SG: 31 CG: 32 | 3T Siemens Skyra FSL (FIRST, FAST) | ↓ Whole-brain grey matter, white matter, hippocampus, thalamus, pallidum (↔ after correction to TBV) Cortical injury on neonatal MRI connected with ↓ hippocampus, thalamus, grey matter, white matter (only ↓ hippocampus after correction to TBV) |

| Pfister KM et al., 2023 [11] | 5 years | SG: 10 CG: 8 | 3T Siemens Prisma Freesurfer v.6.0.0 | ↔ TBV ↓ Hippocampus R and L (about 10%) ↔ Thalamus, putamen, caudate nucleus, amygdala, posterior hypothalamus ↓ Hippocampus → lower memory function |

| Im SA et al., 2024 [12] | median 10 days | SG: 107a CG: 83 | Not specified Aquarius iNtuition | ↓ Brainstem ↑ Ventricle ↔ Intracranial, cerebellar, cerebrum Among SG: ↓ brainstem, cerebellar, intracranial; ↑ ventricle, ↔ Cerebrum – in abnormal neurodevelopment group compared to normal neurodevelopment group (neurodevelopment measured at 18-24 months) |

| Annink KV et al., 2021 [13] | First MRI at 4-5 days, second at 10 years of age | SG: 50 (22 – TH) CG: 0 | Neonatal MRI (non-TH group): 1.5T Neonatal MRI (TH group): 1.5T and 3T Philips At 10 years of age: 3T Philips Freesurfer v.6.0.0 | Neonatal MB score: normal → 9% atrophy at 10 years of age Neonatal MB score: equivocal → 10% atrophy at 10 years of age Neonatal MB score: abnormal → 76% atrophy at 10 years of age Atrophy of the MB on neonatal MRI → ↓ hippocampus and parahippocampal white matter ↓ Hippocampal → impaired total intelligence quotient, performance intelligence quotient, processing speed, visual-spatial long-term memory, verbal long-term memory at 10 years of age |

| Wu CQ et al., 2023 [14] | First MRI at 4-15 days, second at 6-8 years | SG: 23 (35 for cerebellum width grown)b CG: 26 | At 4-15 days: 1.5T Siemens Symphony At 6-8 years: 3T Siemens Skyra SPM12 (SUIT pipeline) | ↓ TBV, raw cerebellum at 6-8 years (about 6%) ↔ Cerebellum after correction to TBV at 6-8 years Reduced growth of cerebellum width in children with cognitive impairments (FSIQ ≤ 85) compared to those without |

MRI – magnetic resonance imaging, SG – study group, CG – control group, R – right, L – left, TH – therapeutic hypothermia, TBV – total brain volume, MB – mammillary bodies, FSIQ – Full Scale Intelligence Quotient, ↓ – reduced, ↑ – increased, ↔ – no difference

Hippocampus

The hippocampus plays a role in learning and memory, spatial navigation, emotional behavior, and regulation of hypothalamic function [15]. Within the hippocampal formation, heterogeneous vulnerability to injury has been observed [16]. The cornu ammonis 1 (CA1) region of the hippocampus is considered to be the most susceptible to damage, followed by cornu ammonis 4, cornu ammonis 2, cornu ammonis 3 (CA3), and dentate gyrus [17]. However, a recent review of studies on the hippocampus indicated that cell damage may be more pronounced in the CA3 region, occasionally exceeding that observed in CA1 [18]. Studies suggest that the hippocampus is particularly sensitive to hypoxic injury [19]. A study by Kasdorf et al. [20] reported that TH does not provide effective neuroprotection for the hippocampus in the context of hypoxic-ischemic injury.

In a study of neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, considering total brain volume (TBV), there was a significantly smaller volume of the right hippocampus (p < 0.001) compared to the control group, while the difference in left hippocampal volume did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.09) [9]. Subsequent studies by Pfister et al. [11] and Spencer et al. [10] suggested that a reduction in hippocampal volume occurs at a later age.

In children at 5 years of age, the hippocampus was approximately 10% smaller in children with HIE. The reduction in hippocampal volume was statistically significant across the whole structure (p = 0.02), as well as in the left (p = 0.03) and right (p = 0.01) hippocampus. This difference persisted when the total intracranial volume was taken into account (p = 0.008 for the whole hippocampus). In addition, smaller volumes were observed in the topographic subdivisions of the hippocampus, including the head (p = 0.03), body (p = 0.008), and tail (p = 0.03). Hippocampal subfields, such as cornu ammonis fields (p = 0.01), subiculum (p = 0.04), and dentate gyrus (p = 0.006), were also found to be smaller. Smaller hippocampal volumes were associated with lower memory function in children with HIE [11].

Children with HIE aged 7 years showed significantly smaller raw hippocampal volume compared to healthy controls (p = 0.004). However, when considering TBV, the group differences were no longer statistically significant (p > 0.05). Nevertheless, hippocampal volume remained significantly correlated with cognitive performance (r = 0.477; p = 0.010) as measured by the full-scale intelligence quotient (FSIQ) and motor function (r = 0.526; p = 0.004), indicated by Movement Assessment Battery for Children, Second Edition (MABC-2). Furthermore, children with cortical lesions visible on neonatal MRI exhibited significantly smaller hippocampal volumes at school age (p = 0.001), and this association remained statistically significant after correction for TBV (p = 0.002) [10].

The association between smaller hippocampal volumes and impaired total intelligence quotient, performance intelligence quotient, processing speed, visual-spatial long-term memory, and verbal long-term memory was confirmed in children at 10 years of age [13].

Current evidence indicates that the hippocampus is particularly vulnerable to the effects of HIE. Volumetric alterations can be detected in early childhood and tracked across development. Although hippocampal volume differences are not always statistically significant after adjustment for TBV, their consistency across studies and their association with cognitive and motor impairments suggest that hippocampal injury may be functionally meaningful. Moreover, evidence from other clinical populations, such as patients with depression, also links smaller hippocampal volumes to cognitive deficits [21], further emphasizing the importance of this structure in neurocognitive function. Inconsistencies in statistical outcomes, such as those observed at age 7, may reflect that hippocampal volume loss is, in part, secondary to broader brain growth disturbances. Nonetheless, the association between hippocampal volume and neurocognitive outcomes suggests a potential role for the hippocampus as a selectively vulnerable and clinically meaningful structure.

Collectively, these findings not only confirm the hippocampus as a site of early vulnerability but also suggest its potential as a marker of long-term neurodevelopmental risk. Importantly, they raise the possibility that early hippocampal changes detected by MRI, particularly within the first week, could serve as a prognostic indicator, given their apparent continuity with reduced hippocampal volumes and impaired function in later childhood. However, this hypothesis requires confirmation in well-designed prospective studies. This potential predictive role is especially relevant in light of the limited hippocampal protection offered by current therapeutic approaches, underscoring the need for future interventions targeting limbic system preservation. This insight may help identify children who would benefit from early intervention strategies aimed at supporting future cognitive development.

Thalamus

Historically, the thalamus was viewed primarily as a passive relay station for sensory and motor information, simply passing signals between subcortical regions, the cerebellum and the cortex. However, more recent research has revealed that the thalamus plays an active role in higher cognitive processes, including attention, memory, and information processing speed, functioning as a critical node in integrated brain networks connecting cortical, subcortical, and cerebellar circuits [22,23]. The thalamus is an area that is particularly vulnerable to damage from hypoxia [24]. Furthermore, the volumetric development of the thalamus has been positively associated with both receptive and expressive language abilities [25].

In neonates with HIE, MRI scans conducted during the first week of life revealed significantly reduced volumes of both the right (p < 0.001) and left (p = 0.002) thalamus when compared to healthy controls [9].

Spencer et al. [10] observed significantly smaller thalamic volumes (p = 0.013) at around 7 years of age; however, this difference was no longer significant after correction for TBV (p > 0.05). Correlations were found between thalamic volume and FSIQ (r = 0.452, p = 0.016) and MABC-2 total scores (r = 0.505, p = 0.006). Moreover, patients with cortical injury on neonatal MRI exhibited significantly reduced thalamic volumes (p = 0.002); however, after false discovery rate correction, this association was no longer significant.

Additionally, another study failed to demonstrate any significant alteration in thalamic volumes in 5-year-old children [11].

The available evidence suggests that the thalamus may be susceptible to early hypoxic-ischemic injury. Volumetric reductions were observed both in the neonatal period and later in childhood. While some studies indicate that these differences did not remain statistically significant after adjusting for TBV, their association with cognitive (FSIQ) and motor (MABC-2) outcomes suggests that thalamic development may play a role in neurodevelopmental trajectories following HIE. Nevertheless, the lack of consistent volumetric findings at later ages, such as at 5 years, raises the possibility that observed changes in early scans may reflect transient alterations or secondary effects of more diffuse brain injury. Future research should aim to clarify whether thalamic injury in HIE represents a primary and functionally meaningful lesion, or whether it is a downstream marker of global developmental impairment.

Cerebellum

The cerebellum is traditionally associated with motor coordination and balance. However, recent studies have provided increasing evidence that its functions extend far beyond motor control [26]. Owing to its extensive connections with the cerebral cortex, limbic structures and basal ganglia, the cerebellum plays a pivotal role in modulating emotional regulation, motivational states and higher cognitive functions [27]. The cerebellum has not traditionally been considered vulnerable to hypoxic-ischemic insults due to its relative distance from the initial injury site. Emerging evidence from experimental models suggests that cerebellar injury may indeed occur following experimental hypoxia-ischemia [28]. Notably, recent findings indicate that the cerebellum can sustain damage in term neonates after birth asphyxia, even when treated with TH [29].

In the first week of life, a reduction in right cerebellar hemisphere volume was observed in neonates with HIE compared to healthy controls (p = 0.02). The left cerebellar hemisphere did not differ significantly (p = 0.2) [9]. No significant differences in cerebellar volumes were found between children with HIE and healthy children at 10 days of life (p = 0.660). Importantly, no difference in cerebellar volume was observed between HIE children with abnormal development and healthy controls (p = 0.660). However, children with HIE with abnormal neurodevelopmental outcomes at 18-24 months exhibited significantly smaller cerebellar volumes on MRI performed within the first 10 days of life compared to those with normal development (p = 0.002) [12].

Another study, conducted by Wu et al. [14], investigated cerebellar development from 4-15 days of life to 6-8 years of age. Total cerebellar volume was approximately 6% smaller in the HIE group compared to healthy controls (p = 0.0236) at the age of 6-8 years. However, this difference was no longer statistically significant after normalization to TBV (p = 0.3417). The authors also examined cerebellar growth trajectories from the neonatal period into childhood. Reduced growth of cerebellum width was observed in children with cognitive impairments (FSIQ ≤ 85) compared to those without (p = 0.0005). Additionally, FSIQ score was more strongly associated with interposed nucleus volume in the HIE group than in controls (p = 0.0196).

Overall, the cerebellum plays a critical role not only in motor and cognitive functions across neurodegenerative conditions, but also in reflecting clinical decline. In Alzheimer’s disease, smaller cerebellar volume is associated with worse executive dysfunction [30]. In multiple sclerosis, it may predict future disability, particularly in dexterity and processing speed [31]. In the context of HIE, reductions in cerebellar volume have also been reported, although the patterns and timing of these changes differ from those seen in neurodegenerative conditions. Early MRI scans of neonates with HIE do not always reveal significant cerebellar changes. However, studies suggest that reductions in cerebellar volume may have prognostic value for long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes. The observed relationship between cerebellar growth and cognitive performance may reflect the cerebellum’s known anatomical and functional connections to cognitive networks. However, further research is needed to determine whether this association is causal or indicative of more widespread brain injury. Further studies are necessary to better understand how cerebellar injury in HIE relates to the more extensive patterns of brain damage and whether targeted interventions can mitigate these effects. If validated, cerebellar volume reductions could become one of several imaging biomarkers to support early risk stratification and guide future interventions in infants with HIE.

Basal ganglia

Classically, the basal ganglia are considered to be a group of subcortical nuclei, including the striatum (caudate nucleus and putamen), globus pallidus, subthalamic nucleus, and substantia nigra [32]. The basal ganglia are primarily involved in motor control and motor learning, but they also contribute to procedural memory formation, particularly in habit and skill learning, executive functions, emotions, and behavior [33,34]. In clinical neuroimaging of neonates with HIE, injury to the basal ganglia and thalami (BGT) represents one of the hallmark patterns evaluated in conventional MRI scoring systems. This injury has been consistently linked to increased odds of both cognitive and motor impairments in later childhood [35]. Motor impairment severity in full-term infants with HIE has been shown to correlate strongly with the extent of basal ganglia injury, particularly within the striatum [36].

Volumetric analyses in neonates with HIE have revealed significantly reduced basal ganglia volumes (p < 0.001) during the first week of life [9]. However, the long-term trajectory of these alterations remains unclear. By age 5, the volumes of the putamen and caudate nucleus did not differ significantly from those of healthy peers [11]. Moreover, reduced globus pallidus volume (p = 0.026) was reported in school-aged children at 6-8 years of age, though this difference lost statistical significance after normalization to TBV [10].

When considered together, early reductions in basal ganglia volumes, observed during the first week of life, may reflect initial structural alterations. However, the clinical significance of these changes remains uncertain without integration into broader diagnostic frameworks. While some studies demonstrate normalization of basal ganglia volumes in later childhood, it is unclear whether this reflects true recovery or neuroplastic processes. Neurogenesis has been demonstrated in the human striatum [37]. In the context of TH, current clinical findings suggest that brain plasticity is not significantly impaired in the long term, provided the intervention is applied within standard treatment parameters [38]. Thus, while basal ganglia plasticity holds promise as a mechanism of recovery, further investigation is needed to clarify its nature, direction, and clinical significance in neonates with HIE. Further inquiry is needed to explore whether early volumetric reductions in basal ganglia correlate with conventional BGT injury scores and long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes. Such studies may improve prognostic precision and identify children who could benefit from targeted intervention strategies.

Discussion

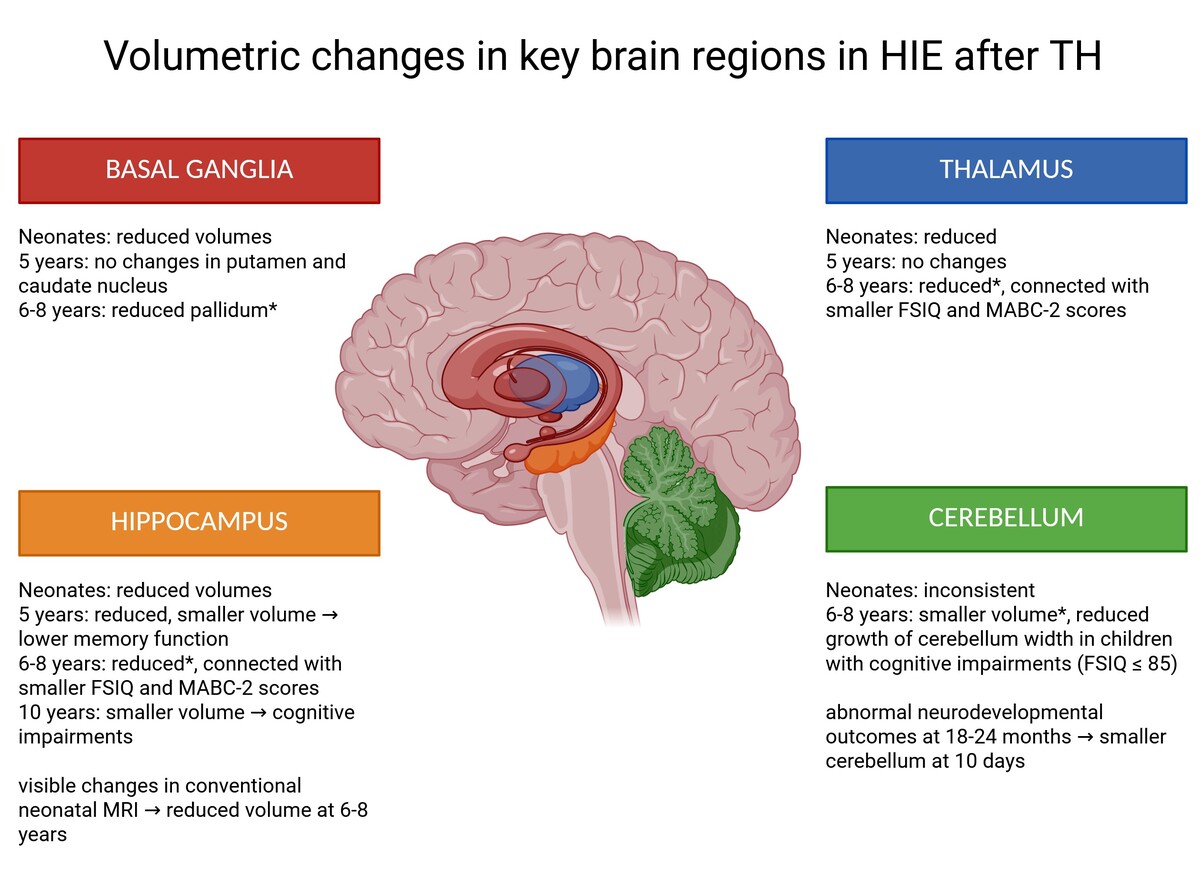

This review summarizes the findings that highlight consistent volumetric reductions in several key brain regions in children with HIE treated with TH. Across multiple studies, the hippocampus, thalamus, cerebellum, and basal ganglia emerge as the most frequently affected structures. A graphical summary of volumetric changes in these structures is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Volumetric differences in hippocampus, thalamus, cerebellum and basal ganglia in children with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy after therapeutic hypothermia. Figure created using BioRender.com (accessed on 12 July 2025)

Although the magnitude and statistical significance of these volumetric differences vary across studies, a recurring pattern suggests selective vulnerability of these regions to hypoxic-ischemic injury. Importantly, volumetric alterations in these structures have been linked to adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes, including deficits in memory, cognitive performance, motor function, and executive skills.

Among these structures, the hippocampus appears particularly sensitive to early injury. Volumetric reductions were detectable in both the neonatal period and later in childhood. This finding is of special interest, given the role of the hippocampus in memory and learning, and its previously reported resistance to neuroprotection by TH. Similar vulnerability has been observed in the thalamus and basal ganglia, especially within the striatum and pallidum. However, some volumetric differences have been shown to lose statistical significance after correction for TBV. The interpretation of volumetric reductions relative to TBV remains challenging. It is unclear whether neurodevelopmental deficits are driven by absolute regional volume loss or by disproportionate reductions relative to overall brain size. Given the intricate connections between brain regions and their overlapping functions, it remains difficult to attribute specific neurodevelopmental deficits to isolated volumetric reductions in single structures.

An important consideration that may influence the accuracy of brain injury assessments in HIE is the timing of MRI after TH. Diffusion-weighted imaging demonstrates the highest sensitivity for detecting injury during the first week of life, with pseudonormalization of diffusion occurring after day seven [39]. Conversely, signal abnormalities on T1- and T2-weighted sequences tend to become more apparent between the first and second weeks of life [40]. This dynamic evolution raises the possibility that performing volumetric MRI assessments after completion of TH – around day seven of life – may represent an optimal diagnostic window. If normative volumetric data for neonates at this time point were established, early deviations in the hippocampus, thalamus, basal ganglia, and cerebellum could potentially serve as predictive markers for long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Despite these insights, several limitations must be acknowledged. The studies included in this review employed heterogeneous methodologies. Different MRI scanners and segmentation techniques limit the comparability of volumetric findings across studies. These methodological differences are particularly relevant when examining brain volume measurements, where variations in MRI field strengths and the choice of segmentation software can introduce biases. A study using FSL-FIRST demonstrated that 1.5T and 3T MRI scanners cannot be interchangeably used for determining the volume of subcortical deep gray matter nuclei [41]. Combining data from different MRI devices with varying field strengths introduces volume biases, with the magnitude and direction of the bias depending on the specific brain structure and MRI vendor-field strength combination [42]. Another study showed that Freesurfer, FSL, and SPM provide satisfactory robustness in volume measurements across field strengths, with only minor performance differences, particularly for certain tissue compartments and intracranial volume [43]. Furthermore, when using the same MRI scans, it was demonstrated that Freesurfer and FSL-FIRST are not interchangeable for volumetric data [44]. These findings underscore the importance of standardized methodologies in volumetric studies. Differences in participant age at scanning, as well as in the neurodevelopmental outcome measures used, further complicate direct comparisons and synthesis of results. Moreover, most studies were conducted in small, single-center cohorts, limiting statistical power and generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, few studies have established longitudinal volumetric trajectories or validated volumetric measures against functional outcomes across different developmental stages.

These findings also raise important questions about the potential clinical utility of volumetric MRI in routine care. While MRI remains a cornerstone in the assessment of neonatal brain injury, the integration of advanced volumetric analyses could enhance prognostic precision. However, in the absence of established normative values and validated predictive models, it remains difficult to translate volumetric findings into concrete clinical recommendations. Developing accessible, automated tools for volumetric measurement in the neonatal brain and establishing normative databases will be critical steps toward translating volumetric MRI from research to clinical practice.

Conclusions

Volumetric reductions in the hippocampus, thalamus, basal ganglia, and cerebellum are consistently observed in children with HIE treated with TH. These alterations are linked to cognitive and motor outcomes in later childhood. Nevertheless, it remains uncertain whether these volumetric differences reflect direct injury to specific structures or are secondary to global brain growth disturbances. Early volumetric assessment may represent a valuable prognostic tool, offering opportunities for earlier intervention and improved neurodevelopmental monitoring. Future studies should validate volumetric biomarkers in prospective cohorts, refine segmentation methodologies for the neonatal brain, and explore the potential of integrating volumetric MRI into early diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms for children with HIE.